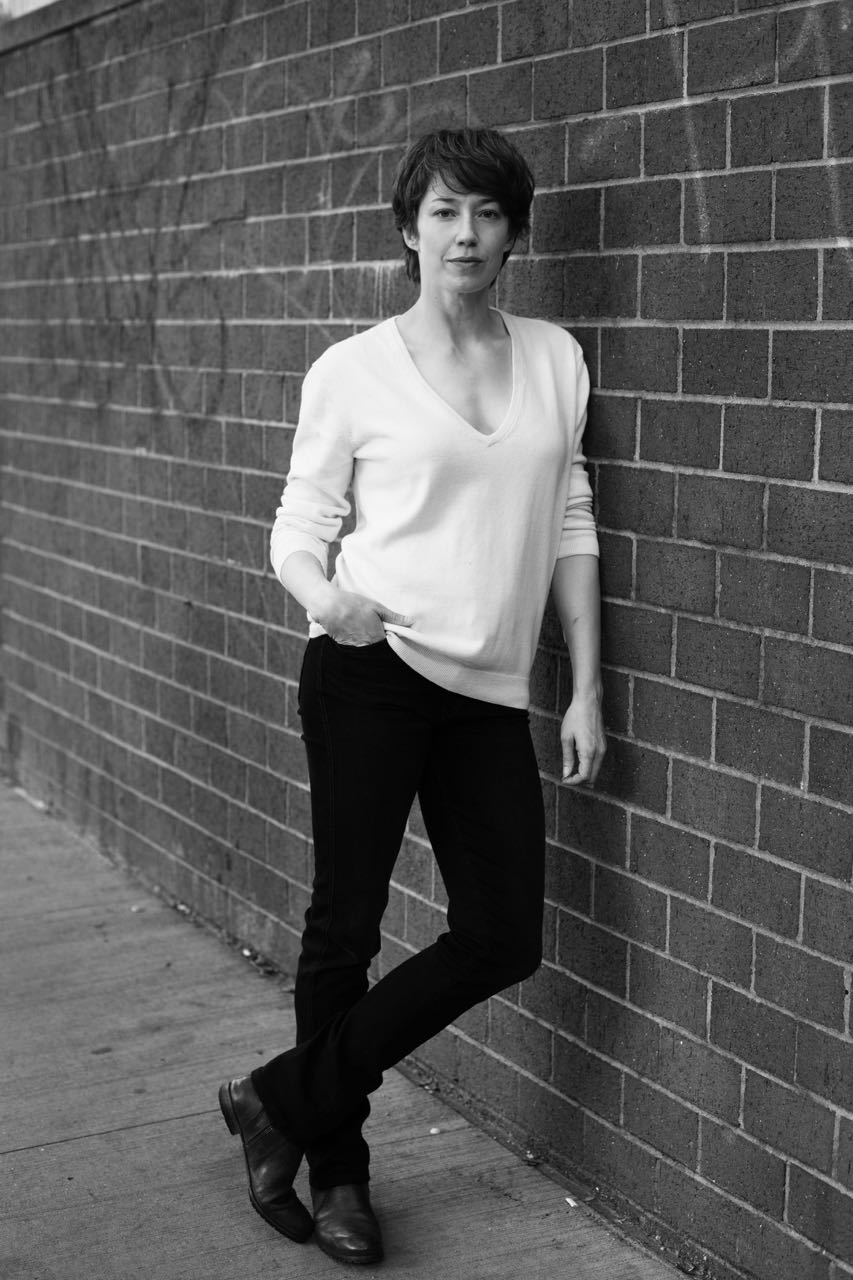

Carrie Coon, Liza Colón-Zayas, Danaya Esperanza, Susan Pourfar, and Brenda Wehle on “Mary Jane”

Written by Victoria Myers

Photography by Tess Mayer

September 21st, 2017

The new play Mary Jane by Amy Herzog and directed by Anne Kauffman, currently having its New York premiere at New York Theatre Workshop, centers on a woman trying to care for her chronically ill child. Carrie Coon leads the cast in the title role, and features Liza Colón-Zayas, Danaya Esperanza, Susan Pourfar, and Brenda Wehle, each playing two characters. We recently sat down with the five women of the cast to discuss their process for the play, learning to be themselves in the rehearsal room, and being in a play where the cast just happens to be all women.

For each of you, what was your way into your characters? And for those of you who are playing multiple characters, how did you approach that?

Liza: The first character that I play is a home care nurse. I mostly tried to draw upon the home attendants that have been caretaking my mom and my grandma for decades. And I noticed that the nurses who they felt the most comfortable with were the ones who were efficient and truly wanted to engage, and that my mom or my grandma felt like they could adopt. That’s something that was already on the page and that the director and the writer certainly were guiding me towards, but it’s easy to have that to draw on. And the doctor just went to hospitals and observed and saw the different types of personalities.

Carrie: I did a reading of this play in Amy’s living room about two years ago. It was a very early draft with a bunch of actors and it was a lovely time. The play was in its infancy then. But Amy and I had talked about the possibility of getting to do it sometime down the line. The thing that I really loved is that it wasn’t maudlin or sentimental and that Mary Jane had a very natural exuberance. I usually get cast in roles that are quite lugubrious and heavy and my family finds that really inexplicable. So in some ways Mary Jane was a lot closer to me as a person than a lot of the other things I’m known for playing now on TV—all two things that I play on TV. So I was very interested in the play and I was disappointed I wasn’t able to participate in the earlier iteration. But they had a fantastic group of actors and they learned a lot about it, and we are really benefiting from that previous work. Amy and Anne really understand the play now, and I think working on the play with a new group of actors has enhanced that. As Anne would say, we just ask different questions than the other actors asked, which takes the play in a different direction. So much of who Mary Jane is, is on the page. It’s in Amy’s writing, which is very specific and very deft. And so, for me, it’s about relaxing into the language and trusting those rhythms that are already built into the piece, and not being afraid to allow myself into that person. She’s actually a lot closer to me than some other characters I’ve played even though the circumstances are not close to my own personal life.

Susan: I play two different women who are both moms that have children who have diagnoses where we don’t know what the diagnosis is, and I come into contact with Mary Jane. One of the characters is in the same hospital [as her] and one of them gets advice about what’s the best course of action if you have a child with disabilities. I have a newborn and my way into this entire process has been through sleep deprivation. Mary Jane says, “I used to be a person who thought I can’t survive without sleep.” But for me, this has been a process about figuring out how to be a mother in my actual life and then come here and play these moms. I am drawing a lot on what it is I’m actually going through right now. The very beginning period of first coming home with a baby is so raw and vulnerable. I also have wanted to work with Amy Herzog for a long time. I’ve loved everything that I’ve ever seen or read of hers. When Anne first reached out to me [about this play], it was basically a yes without even having read it. It was just like, “I want to work with you. I want to work with Amy. Consider it a yes and I’ll read it later.”

Brenda: I had the exact same reaction that Suzy had: Okay, yes, and then reading it. I play two different characters, as everyone does, except Mary Jane. I don’t have any familiarity, really, with either one, but what I do to enter the process is listen first. Reading. Listening. Listening as each character that I’m playing and also listening to how others hear the characters that I’m playing. That to me, in this day and age, is harder and harder and harder to do. So it’s a great gift to be able to exercise it that way. It’s such a lovely, beautiful, rich, honest, supportive play. Every character in it is really trying to give their everything to whatever their life is bringing to them and to others who need them. These characters need each other in really interesting ways. That aspect of it was really illuminating to me in reading it. It doesn’t mean everybody’s life is simple in the play. But it’s the way in which people relate to each other and how they are there for them. It’s just a beautiful thing to be able to do on stage. People are trying their best.

Danaya: I read the play before I auditioned for it. I did a play of Amy’s, The Great God Pan, in grad school, and she came to one of our rehearsals and she came to the play. So I had met her and I had just worked with Sam [Gold], her husband, on Othello. I was understudying, so I had been seeing her around and then I was really excited to audition for this play. My way in was through the script and through the language and also drawing on her other work, which she talked about in our other rehearsals. And the way that she structures her plays. I auditioned with a completely different idea of one of the characters, Sherrie’s niece Amelia. I drew a lot on what Sherrie says about her, and then when we started the rehearsal process it completely flipped. I think every couple of days I came in with new ideas, which I think is a testament to Amy’s writing. These are real people and these words can come out of anyone’s mouth. It’s amazing how this language can fit so many different types of people. It was really about what kind of dynamic we wanted in this production. I have a sense that the Yale production was completely different. But this was closer to who I am. Anne kept saying that we really want to see the actors through the characters and different parts of ourselves. Like, “What is it if we magnify this part of you in this character? And what is it if we magnify this part of you in this other character?” But it’s all stemming from who you are as a person, which I think is a great way to approach acting in general, but it was really wonderful to get that kind of freedom.

Carrie: And a testament to Danaya, as a young actor that she came to rehearsal with ideas instead of waiting for someone to tell her what to do. That’s actually really rare.

Do you all like coming into rehearsal with a lot of ideas and work you’ve done at home?

Liza: You have to. That’s part of your job.

Carrie: Certainly some directors are more prescriptive, I would say. But your job is partly to come in having explored the character.

Danaya: For me, it is about bringing an idea. The text gives me ideas so I don’t know how I could come in without any ideas.

Carrie: It’s possible, believe me. I’ve seen it happen. I don’t mean to be critical of young actors. What I’m really saying is sometimes it takes, particularly women, a long time to get out of the practice of waiting for approval. And I’m very impressed with Danaya coming in with her proposal for what’s next. It’s actually something I do think is unusual for somebody as young as she is and as early in her career. It took me a long time to unlearn that behavior as a woman. I had a director when I was quite young, just out of grad school and working in rep, who after a day of rehearsal, said, “I am actually really interested in working with Carrie as the actor, not Carrie the good student.” And I was like, “Oh, right.” And that was a really instructive day for me. It made a lot of sense to me, because I think we’re taught from a young age, as women, to look for approval. To say yes to everything and wait for what we’re supposed to say yes to.

Have any of the rest of you had experiences like that? Or a process you had to go through of figuring out how to stand up for yourself in a rehearsal room or come in with ideas and not be looking for approval or trying to be likable?

Susan: I think everyone has, in their early years, the voice of a teacher in their head. I had a wonderful teacher, but her voice was strong and critical. I remember having this eureka moment during a show that she had come to and it was like, “I’m done with that. I know now. The only voice I’m listening to now is my own.” That’s not to say there are not times when you don’t feel like you need guidance—I’m all for going to people for guidance—but when someone else’s voice is stronger than your own, it limits you.

Liza: As women and as women of color, there’s always that challenge. I live with it 24/7. So I’m always trying to hear something and see, “Am I hearing it through that filter? Am I hearing it through a filter of being insecure? Or can I just trust these people in the room?” And I do. And it actually made it challenging in a different way for me to trust what I was doing. Because I had so much admiration and safety and there were a lot of different ideas. I came in doing one thing and ended up doing a whole other thing. But that can happen. I can do that and explore if I feel a level of mutual respect. And that’s what I found here. For me, there’s always some level of insecurity, but it became a different kind of insecurity of learning to just work in a different way. And I look at my cast and see how amazing they are and how they’re rolling with it. With theatre, I’m used to a longer period of table work and trying to find how we interact together. This was a fast rehearsal period, so there was that level of, “Oh, am I approaching this right?” And I want to get it right because the story is so good and because the cast is so good. But I think that I’ve had a breakthrough. We come in with ideas, but I think the industry and society and life experience puts extra layers on it that we have to learn to either trust or learn to release and jump into the deep end.

Brenda: I was just listening to a podcast this morning from the Rubin Museum. And this man was a secular Buddhist, and he was talking about how what they do at the Rubin Museum is they take one of the pieces of art, and then somebody comes in and does a talk on it and then you meditate on it. The one today was Tara the Goddess of Compassion. And there are two different ones. There’s a white Tara and there’s a green Tara. And the green Tara is a statue, and she’s just about to get up, she’s ready to leap into action. And the other one is more withdrawn and just compassionate. But this one is set to go. And I was so struck by the idea of that as a creative impulse. For me, it feels like you come in with all kinds of things. It’s not one or the other. You come in with great insecurity and you should because, honestly, it’s uncreated, so you really don’t know. You have to listen very carefully and very deeply. You’re learning all the time. And that assembles itself into the creation of a production of this play written by Amy. And I feel like we’re still about to get up into place. Even when you go out there and you go, “I’m not sure I’m ready to get into place yet,” but you do. You take the leap.

Do you find with doing something that’s contemporary and an all-female cast, that there are hidden challenges to it in terms of worrying about the audience’s perception that the characters might be closer to you or closer to people in their real lives?

Carrie*: I can’t necessarily speak to that, but I can say that it feels political to be in a room full of women. It feels political to be a woman. It feels political to be telling a story that feels so female in its gaze. Especially now. And I think that, actually, is the anxiety. It really doesn’t have anything to do with the way the audience will perceive us, or me, or Mary Jane. It feels like a big fuck you to stand in a room and tell a story with a bunch of women right now. Not that there’s hostility in it. Actually, I think the lesson is that there’s great generosity in it. We are taught that women are catty and judgmental when, in fact, my experience of being in a room full of women is there’s always generosity and learning inherent in that. It contradicts everything I’ve been taught and I’m moved by the act of being here every day, because of what we’re acknowledging that we’re experiencing and that we’ve always been experiencing, and we’re finally having conversations about it when maybe we haven’t before. And that just feels like a political act in and of itself.

Danaya: I agree. I was talking to Linda [Chapman], the Associate Artistic Director, after our first preview, and I said it’s actually really refreshing to be in a room with people of different ages, ethnicities, and races. And to be a woman of color in this room and in a play where my being a woman of color is not the focus of the play—that I am not representative of my race. And that it’s about people being together and trying to connect. We’re trying to connect and we’re trying to understand each other and gain understanding of ourselves through other people. That is what I’m experiencing in the room every day, and also, that’s this play. This is a world on stage that we don’t see as often. And I don’t feel like there’s anything missing.

Liza: I try not to judge. I don’t approach a character judging how the audience is going to see it. If I feel that inkling, I don’t take the role. If I feel like it’s too easy to make this person a stereotype or insulting, or if I feel like the director is trying to do that, I’ll fight against it. I want to believe in what I’m doing, and so hopefully everyone else will believe in what we’re doing.

Susan: I actually forget a lot of the time that we’re in an all-female cast. It’s not the log line I would use to describe it to someone. When I’ve been asked, “What’s the play about?” I’ve never once led with, “Well, it’s a group of women,” because it feels to me that there are so many colors—so many real and specific people on stage that it’s just not the foremost thing in my mind. There are people in different economic classes in this play, like ranging from a superintendent to a very powerful doctor in a hospital. It runs the economic ladder up and down, which I don’t often see. I see plays about the working class. I see plays about a bunch of wealthy people on the Upper East or West Side. But I don’t see plays where there’s this intersection of people coming from all different income brackets and be all meeting—

Carrie: And that’s not the focus of the play.

Susan: That’s not the focus either. There’s the very middle class situation of the nurse. There’s maybe the most subtle class consciousness/conflict in maybe one or two instances, but not spoken. Which is, I think, true of life in New York City.

Danaya: Which I think makes it even more political. Because it feels real. I think it raises questions because of the time we’re in. We’re reading so much about what is happening economically in this country, what is happening racially, that I think people’s ears just perk up at those lines. Mine certainly do. I go, “That’s what we’re dealing with. That’s what we’re skating around.” Because you don’t often have people having straight on, head on political conversations in everyday life. And there’s something else going on. There are things that are right in front of us. There’s a child that needs to be taken care of, and that is what becomes the most important thing. But all the politics around it are really affecting that. I think that we hear them and we feel them because a lot of us are in the same boat.

What do you each hope that audiences walk away talking and thinking about?

Liza: I just want them to walk away talking about it long after we leave. And I’ve noticed with my friends that have come the last few nights, they just want to talk about these people, and things land in increments. I hope that continues to happen. That’s why I go see theatre.

Susan: One of my characters is a Hasidic Jewish woman, and on a day off I was on a very, very empty beach. It was my family and a Hasidic Jewish woman and her children. I ended up striking up a conversation, and later that night my husband said, “Did that Hasidic Jewish woman help you with the play?” And I said, “No. The play helped me speaking to the Hasidic Jewish woman.” I didn’t even have to think twice to answer him because that’s what I hope for theatre to do: take topics that might be taboo, take topics that might be not in the front of your mind and get you able to converse about it. That’s what I hope it does for other people, is allow for greater conversations.

Brenda: I the energy around the play that I’m experiencing, because I get it from the other actors and all the creative team, is that people are good. And they’re specifically good when someone is open enough to ask them to be good. Or need them. Or help them in some way. They’re available. You know, the world as I see it now makes it increasingly difficult as the demand becomes increasingly huge. This work is an affirmation of the potential for goodness in humanity. It’s just something we need to be reminded of right now, I think.

Carrie: And Amy Herzog does that in such a profoundly truthful way. There’s nothing sweet. It’s very rich. And it’s very layered. And it’s short. And I think the density of the play is really shocking. The way it reverberates after you leave will surprise people. Because there’s so much information packed in to this hour and a half. Because it feels so much like real life. And I think that’s extraordinary.

Danaya: One thing I heard last night, that I hadn’t ever heard before, was how many acts of kindness there are in this play. And it’s not maudlin. It’s the opposite of maudlin. For this woman, for Mary Jane, for each person that she comes into contact with there’s an act of kindness, either that she gives to them or they give to her.

Carrie: It’s not a sisterhood. It’s people. And there’s nothing wrong with a sisterhood—let’s be clear, we need it more than ever—but it’s not about that. It’s just about people in the world bumping up against each other.

Brenda: It’s like your souls are talking. Your souls don’t acknowledge what the body is that houses them. But they do recognize one another.

Danaya: And it’s honesty. It’s when you meet someone with honesty, they will meet you back. The kindnesses are not always happy. They’re not always good, but they’re honest. And in that honesty, you don’t want to fight it; you want to meet it with more honesty.

* An earlier version of this interview incorrectly attributed this quote to Brenda Wehle.