An Interview with Paula Vogel

Written by Victoria Myers

Photography by Tess Mayer

April 18th, 2017

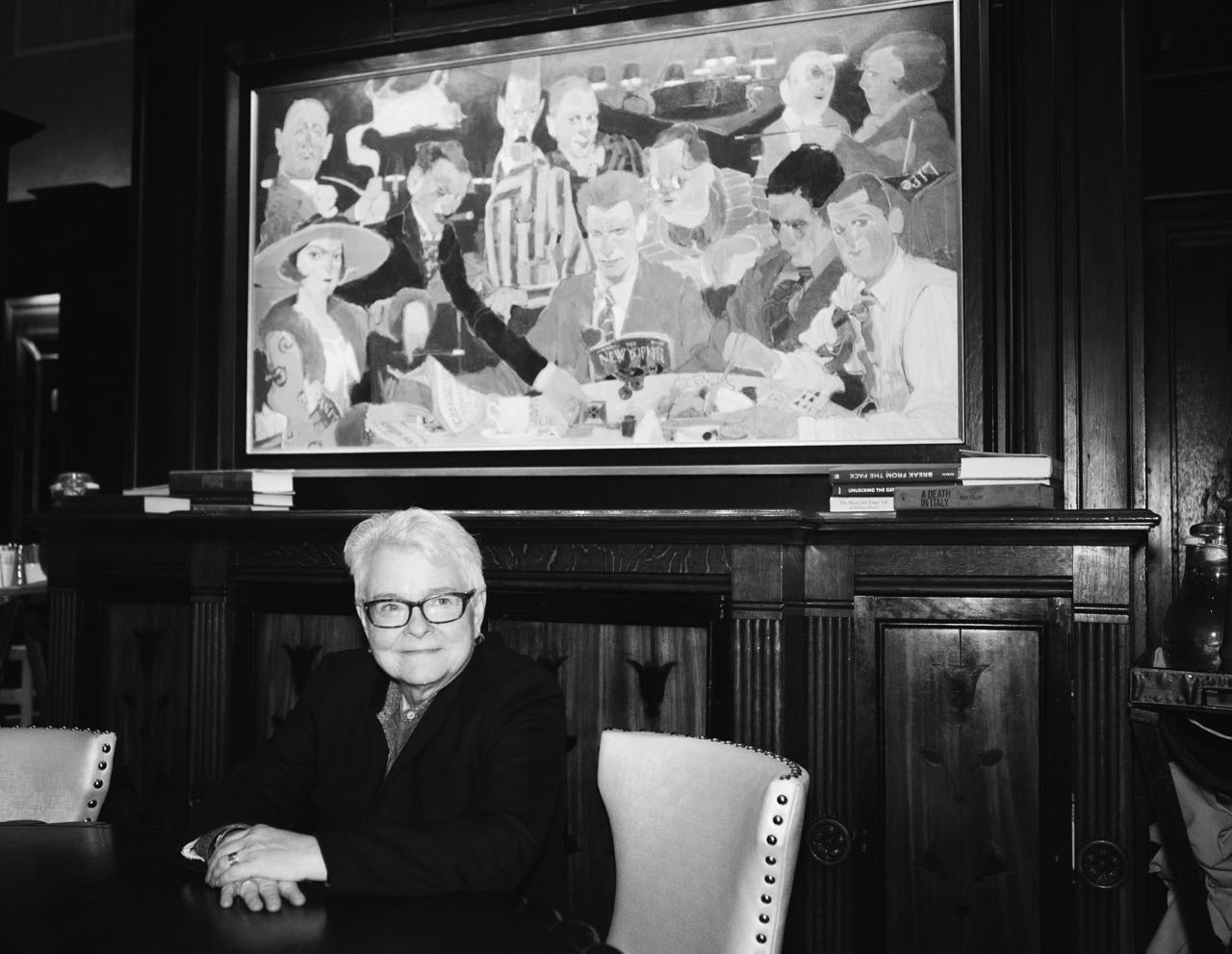

As anyone who follows the theatre probably knows by now, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paula Vogel is making her Broadway debut at the age of 65 with the play Indecent. Indecent is about the turn of the century Yiddish play God of Vengeance by Sholem Asch and the controversy within the Jewish community of how Jews should be represented in popular culture. That, roughly, is the plot—Indecent is very much one of those plays where, if one could easily summarize what it was about, it wouldn’t need to be a play. Indecent had just started previews at the Cort Theatre a few days prior when we met Paula at the Algonquin Hotel, once home to the famous Algonquin Round Table. The table still stands, with a painting of its former occupants mounted on the wall behind it, while tourists buzz around it going about their day. A few tables over, I spoke with Paula about writing Indecent, legacy, ambition, and more.

You’ve spoken about how Indecent was a collaborative process, and not your average experience of writing a first draft and then doing a reading or workshop with the director. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more specifically about how the play was put together and how you found that affected your process as a writer?

I have to say that I think this whole play happened because of [director] Rebecca Taichman’s passion. I had read the play [God of Vengeance] when I was 22 years old. I thought it was stunning. I never forgot it. But Rebecca became obsessed with the play when she read it when she was 26. She held onto this notion of doing a play about the God of Vengeance for 20 years. Now when a really brilliant young artist is that passionate and pursues that dream, that was one of the first reasons that I said yes, I’d like to work with her. The second reason is that I’d already been seeing her work and she’s superb. She’s really an amazing director. I wrote 42 drafts, and every word that I wrote was discussed. When we had workshops, I would go off and I would write until two or three in the morning, and I’d come back in with the new pages and Rebecca would say, “Let’s try it. Let’s try it.” And, in a similar way, she was very open in terms of her process. I was in the room all the time. She would say, “What do you think about that?” And I’d say, “Oh, that was interesting. I’m wondering if we might want to try…” So there was a back and forth.

The other thing that I think was extraordinary was that Rebecca and I designed our production team. I said, “I want a Klezmer band. I’d love to have a clarinetist, a violinist, and an accordion [player].” And we basically pursued the composers and musicians for over three years. We thought and talked about who the choreographer should be.

This is just the closest [collaboration] in my lifetime, and that kind of give and take, where you’re thinking of the entire room as collaborators, takes an incredible leadership from the director. It was the same thing of having basically the same cast for four productions and being able to make tiny little shifts. It’s a fairly complicated machine and it has to look like it’s effortless. That’s hundreds and hundreds of hours from all the artists together, and Rebecca manages to be a conduit for that entire team and she basically goes back and forth between me and everyone in the room. So it’s hard to say specifically. The interesting thing about it is over time we trust each other, and you just end up listening to the play more closely. It’s been an incredible experience.

Did you find that you had to adjust how you were writing, not only in terms of writing for specific actors, but also maybe in terms of writing more quickly than usual or more outside-in than you normally would?

I don’t know that I wrote more quickly. I have this technique called a bake-off where How I Learned to Drive was written in three weeks and The Baltimore Waltz was written in two weeks. So I wouldn’t say that I am particularly slow about it. What I had to do was have a restlessness that I felt Rebecca has [that] it has to be perfect, [that] I could make that a little better. The more that I started to love my troupe and love the artists, the more I wanted it to be the best that it could be. And that meant a patience in terms of going back into the scene and trying other things. That’s the main difference. I’m not working in a vacuum. I could look at actors. One day I was looking at Max Gordon Moore and I said to Rebecca, “I have a crazy idea. I need to disappear for 24 hours.” And I ran home with the collected works of Eugene O’Neill and his letters, and I crammed and came back in the room with a new scene because I thought Max would make a terrific Eugene O’Neill, which it turned out he could. Or having the privilege of working with Katrina Lenk and saying, “I bet I could change her into this character. I bet I could do this.” And the ability to use specific members of the cast who can play musical instruments, but also who can dance, means that you think about how to end the scenes differently. That really informed the writing. I’m writing for the troupe. It’s the way that playwrights used to work back in the 1600s, 1700s, they wrote for the troupe, and oh my God it’s heaven.

This is a piece that has a very strong interplay between form and content. Where in the process did you find the moments of content dictating form, and were there moments of form dictating content?

I pretty much saw the shape of the general play within the first couple of days. It’s why I said yes—I knew I could write it. So I knew where we were going. I knew where the turning point was going to be. I knew what the echoes were going to be. To me, form is content. So, it was a matter of making sure it was the right form. Very early on it was a two-act play. It didn’t work as a two-act play, which meant I had to go back in and make deep cuts. So, it was trying to make that end work; I knew where it was ending. And I don’t really think of [form and content] as divisible. I think they are the same thing.

I think one of the really amazing gifts I’ve gotten from 40 years of working with younger playwrights is that I think the younger generation has a fluidity of storytelling that older audience members may not have. We expect time to behave in a linear fashion. We expect that there’s going to be a beginning, a middle, and an end. But the more that you look at the way plays are being written by younger writers, time is fluid, it’s warping, it’s morphing. I really wanted the dimension of time to change.

Indecent is obviously in relationship to God of Vengeance, but do you also see it as being in relation to other plays and other works of art?

Absolutely, there’s always a homage in everything that I write, usually in every scene. I never have the time to write handwritten notes, so instead I write plays, and I tuck in little valentines within the scenes. Definitely there is a valentine to an astonishing Polish director, by the name of Tadeusz Kantor, who used his childhood in Poland during World War II to create theatrical sculptures about his memory of getting through the war as a child. An astonishing play called Wielopole, Wielopole. And he did a play called The Dead Class, where he remembered his elementary school classmates in this tiny village, but they were basically like Siamese twins, two mannequins of their childhood selves played by their adult selves, and they were all dead, and they come back to life in this classroom. I’ve never seen anything like that. When I told Rebecca that, she came up with the amazing visuals that begin and end the play. There’s a big valentine in this to him. Thornton Wilder, I think I write almost every play with a valentine to Thornton Wilder. The third act of Our Town with the members of the cemetery sitting in chairs in the rain is a huge part of it, and the stage manager, Lemml, is absolutely a valentine to the stage manager of Our Town. And there are many, many more valentines in this. We have an astonishing choreographer, and he’s making valentines to the dances and the dance makers he loves. Lisa Gutkind and Aaron Halva are writing original music looking over their shoulders.

One of the things I found really interesting about the piece is it’s an ensemble piece, but there’s also this way where you have men looking at and writing about women, not just in the character of Sholem Asch, but also Lemml. What was your thought process for using the male gaze within the structure of the piece?

There were a couple of initial impulses that I had. One was that I wanted us all, at the end of the play, to feel that we were native speakers of Yiddish, and that we were in that last audience [of God of Vengeance]. But the second thing was that I wanted us all to recognize how amazing and beautiful female desire is in worlds in which the agency was given to men. The fact that the first scene in the salon, it’s men who are performing the women. I wanted the challenge of, how do I float women through this play and make them concrete and specific with material bodies, but also show men kind of creating a repository of their imagination and their desire?

I’m hoping the fact that women artists have created it makes that somewhat clear. It’s true of every play I write. If I write Baltimore Waltz, for example, I want every man and woman in the audience to think how beautiful the male body is. How could you not be in love with men? That’s a beautiful, beautiful thing. In this play, I’m asking the audience to look at the women in the way perhaps Sholem Asch looked at the women, which was revolutionary in how beautiful women are. The difference is that we’ve changed the characters in the original God of Vengeance, so that it’s not a passive younger woman with an older, more aggressive, experienced woman, but rather that the younger woman is acting on her desires. And that’s a fairly significant shift. How did these women become the agents of their desire, rather than get passively caught in the desire? It’s a beautiful play written by a young married man in 1906 with an astonishing love scene. But I do think it plays differently now, and I think we’re in the 21st century, and I think in order for God of Vengeance to come back into the canon, we have to look at female desire differently, particularly in this country. What’s terrifying is that we are, once again, in risk of policing women and the desire of women, both through things like cutting rights of abortion, control over our bodies, and policing sexuality. That’s where we are.

So in many, many ways, I feel like I’m on just the flip side of the coin that Sholem Asch was showing at a time when the policing was alive and well and extremely dangerous within the Jewish community. And I think of him—he’s a very brave and honest writer for his time. And I’m using him in the present tense because I think of him in the present tense; I don’t think of writers as dead. I don’t think of actors as dead. That’s very much a part of this play. I think the art continues their life force long after they’re gone.

The specter of the Holocaust hangs over the events of the play. How did you work with the fact that you have the audience coming in with a prior knowledge of what was going to happen? When did you want to tap into that, and when did you maybe want to give them the opportunity to forget and think, “Oh, maybe going back to Poland will be okay”?

That’s one of the primary challenges. Our paradigm shifted in the world after 9/11, our paradigm shifted after HIV. You can never go back, and our paradigm certainly shifted after 1938 and the Holocaust. How can we forget that? That was sort of our aim. So one of the aims is to create characters and cast members who don’t know what their future holds, and to present them in such a way that we’re kind of empathizing and caught up in them—through the music, through the dance, through the fact that we’re spending time in struggles that were very real conflicts: Do you cut out the love-making with two women in love, and make it sexual instead? Do you get fired from a production because your Yiddish accent is too strong and you’re going to be replaced, and your lover happens to be your scene partner, right? How do you deal with that? All of that. It’s the struggles we have right now. We don’t know in the next four years how our paradigm is shifting. Our paradigm has shifted since November. We’re on the brink of a paradigm shift. We have to remember the innocence that we have in the moment before the paradigm shifts. That’s my hope. To me, drama is not about what is going to happen, it’s about how did it happen. Can we re-remember? Can we forget what we know, so that we can re-remember what we know in a new light and think, “I didn’t know that. I didn’t realize that impact of it”? So it’s more a reinterpretation.

The other thing I want to say is that what I think is extraordinary right now is this remarkable generation of 21st century audience members and artists and writers and actors, and I love them. I think this is an extraordinary time of theatre. It’s time to retell the story so that I can hear how it’s happening for a new generation. We’re at this point in time when the members in our families, in our society, who remembered the actual events are dying and are no longer with us. We can’t forget. We have to re-witness. We have to reanimate, we have to relive it, and I think this is an important time to do it. So that it’s not thought of as history. It’s a real danger if we think of what happened in 1938 in Germany and Poland and all through Europe as history. It allows us not to notice how we’ve restricted immigration for Syrian refugees. There was a real shudder down our backs with the recent chemical attacks by Assad. If we forget this, we are doomed to repeat it. I think this is a good time to remember. So I don’t think of it as history, and I don’t think of it as past at all.

Does that feel like a greater responsibility?

Not to mention the fact that as I have said, in this moment in time we have to say we are all Muslim. We have to say we are all Latino/Latina. In terms of the hate and the rhetoric: we are all lesbians, we are all transgender. This play said in 1907, “We are all Jewish. We are all women.” Because Sholem Asch really looked at the plight of domestic violence and women. Yes, we feel the responsibility. Responsibility, though, also means how do we live with that knowledge and with some joy and lightness in our hearts, so that we have some resiliency to face what’s happening politically every day? You can’t do it simply by accepting responsibility. You have to think of how to come together and rejoice and celebrate all of the things that are good in our communities. So it may sound strange to be combining those two artistic principles of witnessing and responsibility with celebration and commemoration, but that’s what we’re trying to do as a troupe.

I wanted to talk a little bit about the music in the play, particularly one specific choice. Towards the end of the play, you have the music cue of “Oklahoma.”

Yes. That’s totally mine.

I wanted to ask if you’d talk a little bit about that, especially because it’s this meta moment, since theatre and the entertainment industry were a way in which Jews became a part of American society, and if you go to the Museum of Jewish Heritage, you get to the end of the exhibit, and it basically ends with Rodgers and Hammerstein and Barbra Streisand.

Exactly. In a way, I want us to remember that there was a time in this country in which Jews were not seen as white people. We were not seen as Americans. Nor were Italians or Irish people. There was a moment in time in which we were seen as invaders, foreigners, aliens. When I first wrote that, we went through robust questioning about it, and I kept saying, “I can’t quite articulate why.” I can now. We watch the troupe, and then they’re no more. They’re no longer with us. We decided that that was going to be the end of live music at that moment. But I also want to say the community lives forward. And we tied it in with, “Very few write in Yiddish anymore,” as we’re listening to “Oklahoma.” That we become what is very much considered part of the mainstream, and what it is to be American. So, it’s very important for me. The fact that two Jewish boys from New York could be writing a musical about middle America, the heartland of Oklahoma, and it’s perfectly accepted and celebrated and becomes the most successful long-running musical, I think it’s important. I did want to do that. I wanted it to be recorded song. It’s no longer live. So, it is a moment of history in which whatever the story brings us to, the Jewish impact on American culture is alive and well and continues.

The characters in Indecent are almost all Jewish. Do you feel like there’s anything about the play that is intrinsically Jewish in form?

I feel the process is not just Jewish, it was 19th century in that we became a repertory troupe that traveled together, and we worked on it together, and we went from town to town. We developed a shorthand the way the Yiddish troupes did as they traveled through Europe. We thought about that a lot when we tried to set up a process and get theatres to co-produce together. Do I think there’s anything Jewish [about the form]? This is an interesting thing: I can’t see my fingerprints. I can’t see the fingerprints on the play because I’m in it and I’m too close. It’s the same way that people say, “Oh, your sense of humor.” I can’t see my sense of humor. A lot of people say, “This is a very Jewish sense of humor.” I accept that as a great compliment because we’re not going to survive unless we have a sense of humor, right? But that’s nothing I have control over. I’m kind of really eager to read about what people see when they come to see it. I hope it makes Jews feel really great and proud as a community. I hope my former students feel all of the valentines that I’m writing to them, and trying to think about, “What is this legacy in the 21st century?” They’ve kept me writing for a very long time, because I’m answering back to what they’re writing.

Do you see your plays as plays when you’re writing them?

No, I see them as a journey or an experience, and I guess I feel that I’m the first audience. I start to sound schizophrenic, like all playwrights do. I hear the voices, I see the people—they kind of come to me. I will literally lose my sanity if I don’t, at some point, write it down. So I actually see it as if I’m sitting in a theatre or I’m in the middle of the stage. I don’t know that I think of it as a play. I don’t think of it as literary. I think of it as three-dimensional.

Do you see any themes in your work?

Well, I was just very honored by the 25th anniversary production at the Magic Theater of The Baltimore Waltz. I will never write anything that’s as close to me. I wrote it within a year after my brother died, and it was the first time that I realized what theatre can do—that theatre keeps us alive in the present tense. That everyone is alive onstage. At a point where I couldn’t bear to think that all the words my brother would ever say had already been said, and that his language was finite, I realize that by writing the play, people could say, “Carl is taking a trip to Europe,” instead of “Carl took a trip to Europe.” Is there a parallel to this? Sholem Asch is writing a play. Rudolph Schildkraut is making his entrance. They are still speaking Yiddish. I just went back [to see The Baltimore Waltz] for opening night, and it was kind of like going to a really great wake or funeral for my brother. I very much feel that his spirit is kept alive by it. So I’m hoping that the same thing is true in terms of all of these amazing people that are no longer with us. Oh yes, they are. They are alive and well in the Cort Theatre. And I have to say, performing in the Cort, all of us who love theatre walk on that stage and basically say, “Hello Ms. Hepburn, Hello Eva Le Gallienne,” and even though she’s alive and thank God will be for a very long time, “Hello Cherry Jones. Hello to the cast of Bright Star.” The art forms keep the life force and the energy alive and in the present tense, and I think that that’s probably a consistent theme.

Are you starting to think about your own legacy now?

I don’t think about my own legacy now. I mean, it’s kind of astonishing to me that I’m being done on Broadway. I thought it wouldn’t happen. I have a theory that I’ve very much been seen as a prodigal daughter, and that in our society we have a very deep allegory about the return of the prodigal son, but we have not yet written that allegory for women artists and women comedians, who can criticize and make fun of their fathers’ society and be embraced. If I were going to say, “Gee, I hope there’s a legacy,” I hope it’s the legacy that has been left for me by astonishing writers of the 20th century. Women writers in theatre are pretty recent as an event. So Susan Glaspell, Zoe Akins, Lillian Hellman, Lorraine Hansberry. There are amazing women writing in the 1910s, 1920s, they were very much prodigal daughters. They weren’t embraced for their critique of society as they should have been. So I’m hoping the legacy I leave behind is that it’s easier for both men and women to write something that critiques the present moment in time and that can be seen as a play that is worthy to be on Broadway. You have to realize that since I produced her play when she was 20 years old, I have been incredibly frustrated to see that Lynn Nottage’s magnificent works have not been on Broadway. So I just hope the legacy is that we say that new plays should be the center of Broadway theatre and that I hope that audiences think that this is part of the Broadway season. That’s what I hope. I’m thrilled whenever younger artists come up and say, “I read your plays and they mattered, and I’ve decided to write.” It is an amazing honor. So that’s what I hope my legacy is: that people think of this as a career.

Do you have a spiritual life, and does it affect your work?

I don’t think there’s anyone in theatre who doesn’t consider themselves spiritual. I don’t really know any secularists. In terms of spirituality when it comes to theatre, you are dealing with, literally, the undead. Characters are bringing to life the sense of humans that don’t exist. I consider myself extremely spiritual. I also consider that this past seven years of doing research for Indecent has had an enormous impact, and that it’s a journey that I’m continuing of my own legacy in terms of Jewish culture and Jewish history. That’s been an incredible gift. I consider myself spiritual because I recognize I’m aging, and that’s kind of marvelous to be able to be at a point where the 20-something-year-olds that I’ve been working with are now incredible mature adult writers with their own families and mentoring younger artists. And to see politics and theatre and art and the impact of activism changing. Because the truth is, at my age, I did the [Women’s] March on Washington and I was very, very happy to be in that crowd, but I have to also say I could feel how much my feet were hurting at the end of the day. So I’m so thrilled: it is a spiritual feeling to see how the world spins on. How life continues. You’re aware of that, I think, through age, and along with the pains that we feel in the body. It’s a great gift.

You’re one of the premier teachers of playwriting in this country. Playwriting in academia is a relatively new area. In teaching, where do you land in craft versus theory and what you do you feel is good for writers versus what’s actually not so helpful?

I don’t think prescribing anything is helpful. I don’t think trying to change someone’s voice is helpful. I’ve had a very easy philosophy, which is just find incredible original voices that are all different from each other, and hope that they will come to work with me and influence each other and double dare each other. I think of playwriting more as a poker game than as a solitary act. So I think that when you’re in a room filled with extraordinary minds and thinkers who are trying new things, the worst thing to say is, “No,” or, “that’s not a play.” Or, “you should be doing it this way.” I basically just say, “Show me. Show me, teach me, try it,” and then I just try to provoke people. I double dare you. Who do you hate as a playwright? Okay, I want you to read that person’s work, and then in 48 hours I want you to write fill-in-the-blank’s [with writer you don’t likes name] play. Read all of the work of whoever irritates you. There’s a reason they’re irritating you. In 48 hours you have to do it. Or I assign bake-offs. I’ll say, “Okay, I just want you to stretch your muscles.” I don’t want to change your voice, but I think when we stretch our muscles, we strengthen our voice.

I worked for 24 years at Brown, and literally worked 60 to 100 hours a week. There’s a point in time where it gets harder and harder to write your own plays. And that was the time commitment at Yale. One of the reasons there’s that time commitment is that it was very important for me to see that the playwriting programs in which I taught were free—that there was no tuition charged, and that stipends were given. So for people who would never dream of going to school because they couldn’t afford it, they would be able to teach 18-year-olds or 20-year-olds and just simply write their brains out and quit their three jobs. And there’s something about saying to people, “Brown University or Yale School of Drama believes in you.” I know it’s always a struggle, but if you come your rent is paid. Can you write your brains out for two to three years and do very, very long hours, and where will you be in three years’ time if you can do that? That’s the most essential thing: that art schools should be free, because those artists can mentor the next generation of undergraduates at that school. And there should be a diversity of age and experience in the MFA programs. So the age range at Brown was anywhere from 24 years old to 60. All amazing artists.

A lot has been made about the fact that this is your Broadway debut, and you’ve been asked a lot of questions about that. Do you find that conversation helpful or do you find it begins to be a distraction from the actual work?

Here’s an interesting thing about this: I don’t really know how to answer it. I’m really kind of stunned that it happened. I do recognize the mathematics of being discovered is very different for women and playwrights of color, and very different for gay women. Very, very different. We don’t have models. I think it goes back to what we were talking about earlier of being prodigal daughters. We’re not comfortable as a society with that. We’re not comfortable with African-American filmmakers critiquing a White America, and we desperately need that critique, which is why I’m so thrilled about seeing a movie like Get Out.

One of the nice things about it being this delayed is I’m surprisingly calm because I have to concentrate on the work, and I’ve been doing the work. I’ve been in the theatre since I’ve been 15 years old. I’ve had endless nights of flop sweat along the way where we’re scrambling on maybe a first to second draft to get it up in three week’s time with critics coming in. So has Rebecca. We keep turning to each other and saying, “Ha, we really are concentrating on the work. Everyone on stage is listening to each other very, very hard.” That’s the most joyous and important thing, and I know it may sound like BS, that the process is the greatest joy, but if you don’t fall in love with the process, you can’t sustain the work.

Does it feel any different? I’ll tell you what feels different is I’m a little stunned in the past three nights when I walk to the theatre and I see all these people outside. Because my immediate response is there’s been an emergency or there’s been a fire drill. Why are these people on the sidewalk? That’s sort of my immediate response. I don’t know if that’ll go away. Once I’m inside, I’m home. I’ve been home in 90 seats. I’m home at the Cort. I’m home wherever I can smell that sawdust. That’s where it’s home, and I’m really glad I get to take this off my bucket list. And I also think that, whatever happens, this is going to be the worst post-partum in my life—not to be working with this group of artists. It’s going to be terrible. I’ve never worked with people this long or this joyously before. But, I am also at home with saying, “Okay, that was then. What is now?” Let’s go back into my study. Let’s wipe everything off the table. What’s the next play? And starting on the blank page, I’m going to be at home with that too.

What is your relationship like with ambition? That tends to be a complicated word for women.

It’s a very complicated word for women, and I want to replace it with something else. I want to replace it with the way that I think about ambition and ambition for women, and I want to replace it with what got me through. People may be shocked by this: the only reason I could get through grad school was that during Jimmy Carter’s presidency I could be on food stamps. I have eaten from garbage cans. People are shocked by that. But when you don’t have a home or a family, and you grow up under the poverty line… I’m very ill-equipped to dress for Broadway because until I was 33 years old I never bought store-bought clothing. I don’t see that I had a deprived childhood at all. It really was wonderful, because it was like an incredible birthday party that I could starve being in the theatre instead of starving being a factory worker. So I use the word hunger. The only way that I could get through college when no one in my family had and I worked three jobs, and the only way I could get through grad school when I felt completely unequipped, and the only way I could get through opening nights in my first Off-Off-Broadway shows or Off-Broadway shows when I was wearing my L.L. Bean outlet jacket, was to forget the ambition and just feel the hunger. I think it’s very right to never be satisfied and to always be hungry. Always feel hunger. I feel hungry because I see marvelous works around me and it makes me want to write more.

Am I ambitious? I am ambitious to be the very best writer for the longest period of time, and to write something I’ve never dared to do before. That’s hunger. Will I ever be done on Broadway again? It would be nice. I don’t know. Will people know my name? I don’t know. When people say, “Oh, you’re Paula Vogel,” I think I’m having a high fever and I’m creating some illusion in my sleep and I’m going to wake up in bed. It doesn’t matter, but I know who I am when I’m in a room: hungry to do the next rewrite with the artists in that room. It’s a very grounding thing. Hunger is a great thing.

Are we always going to see that as something that’s not positive for women? I hope there’s going to be so many prodigal daughters in this 21st century. I hope that the Clinton legacy is making so many women really hungry to run for office. Is it ambitious to want to change the country? Is that really ambition? Or is that a hunger? I prefer the word hunger.

Thinking back to when you wrote How I Learned to Drive, did you think then that by 2017 women would be in a different place when it came to equality in the theatre?

I did. Well, here are the statistics. When my first play, Desdemona, was done in 1976, women writers were about 50% of all playwrights and 16% of all plays were produced by women. Three years ago the statistic is up to 22% of all productions. That’s pretty blood chilling. Did I think we were going to be farther along? Yes, I really did. Did I think we were going to be farther along in terms of political representation? In terms of right? Yes. Did I think there were going to be more women faculty members, more women scientists who were visible? Absolutely. And it mirrors the fight against the arts. We have not gotten any further in funding arts as being accessible to everyone. That we have been secluding the arts as a kind of play toy that you need money to see, instead of it being in every elementary school, in every school program, in every neighborhood, in every community center. I thought we were going to be further along. I thought, in this country, it’s always two steps forward one step back. The truth of the matter is it’s been one step forward and one step back. We have to make sure right now that it’s not been one step forward and two steps back. I think we’re going to discover things that are going to be horrible that my generation knew.

I thought I was pregnant in 1970. For a time I was engaged. For a time I was bisexual. I’ve had the privilege and the pleasure to love men. I had a fiancé. In 1970, it was not legal to get an abortion, except in Massachusetts. My fear of pregnancy was so great that I had a false pregnancy. But I remember thinking, “I can’t work my way through college with three jobs and have the child. That’s the end of it.” That’s the end of thinking I’m going to have to find a way to be hungry about something else, to make sure that if I have a child, my child is not hungry. So, I’m a generation that knows what happened to women in the professions without the right to control our bodies. We’re right on the brink. It is not a happy picture. I’m of the generation that knew about the women who died from backstreet abortions.

I also know how the rise in poverty grows when we don’t have family planning. Every child has the right to be wanted. You’re asking if I’m spiritual? Every child, every human being, has a divine spark within them. Therefore, you can never snuff out the divine spark. Every human being deserves to be fed, deserves to be wanted, and deserves to be loved. So that’s where we are right now in 2017. We’re in the danger of going two steps back.

We could have an entire conversation about representation of things like abortion in theatre, because it’s still very antiquated.

It’s very hard to get those plays produced. We’ve been having a benign censorship because the only way right now that we are supporting not-for-profit theatre and commercial theatre is through investment and philanthropy. There are so many things that we have removed from the safety nets in our society that foundations are split: Do we give money for an after-school program with the cuts in education, or do we give $10,000 to a theatre company that’s going to let their doors be open? So therefore, you have to choose very carefully what will not turn off philanthropists from giving their money. And topics like sexuality, lesbianism, anti-Muslim sentiment, abortion—it goes on and on and on—these are flashpoints in terms of American theatre right now, and they have been for some time. It’s something that’s been happening again and again and again. So yes, this is a much longer conversation. To me the miracle is that we’ve gotten the opportunity to say, “Let’s look at the present moment and what we’re doing with immigration and the arts.” In 2017 boy, dye dayenu, that’s a miracle. I’ve thought for years, how would I approach rights to life versus the right to choose, and I can’t wait to read Lisa Loomer’s play on Roe, which I think is extremely needed right now.

What’s something you think the theatre community can do to improve equality for women?

I think we can, as audience members, do exactly what we should be doing to our representatives in the House. Show up and say, “How many women are you doing? How many writers of color? What are your demographics in the audience?” “How many women audience members do you have? You have more than 51%?” You really have to have the courage to say to our artistic directors and theatre companies, whether you’re a man or a woman, “I’m a subscriber. I love the members of my community. How many women are you doing? How many writers of color are you doing in this season? Where are they?” And you have to show up. You have to show up at functions and post-play discussions, and raise your hands and say it. I’m afraid that I may have burnt a bridge or two by doing that on Twitter, but the truth of the matter is, it’s not done out of disrespect. It’s done out of love and concern that our community continues. Our community must continue. We have to represent America on stage, and we’re not representing it.