Searching for Charlotte Zaltzberg: the Legacy of a Lost Female Writer

Written by Shoshana Greenberg

Photography by Jessica Nash

May 11th, 2017

Who was Charlotte Zaltzberg? The question had haunted me for years, ever since I came across her name as the co-bookwriter of the 1973 musical Raisin. Zaltzberg was nominated for a Tony Award for Raisin, a musical adaptation of Lorraine Hansberry’s landmark play A Raisin in the Sun, and Raisin went on to win the 1974 Tony Award for Best Musical.

A woman co-wrote the best musical of the season and was nominated for a Tony? These are major accomplishments for a woman writing musical theatre in any era, let alone the more male-dominated past. And yet, like many women, she had been erased from musical theatre history. Why? Who was she and what was her story?

When I first found Zaltzberg’s name, I searched online repeatedly, hoping I could find enough material to profile her for my Women in Theatre History You Should Know series, but I found close to nothing. Whenever I saw that someone had a connection to Raisin, I reached out to them, asking if they knew anything about Zaltzberg’s life, but they had no information either.

Today, when we want to discover more about a historical personage, we go to our computers. We type the name into our favorite search engine, and, voila, there’s the information we need, perhaps in the form of a bio, a Wikipedia article, and/or an obituary. If information is not available, it’s almost as if the person didn’t exist.

I knew that I must bring Zaltzberg’s story into existence, at least for those of us searching for her online. Her name was out here, it was just the details of her life that were missing.

This is what I did know: She assisted Hansberry’s ex-husband and literary executor Robert B. Nemiroff and worked with him on multiple adaptations of Hansberry’s work. She died at age 49 from cancer, just as Hansberry did at age 34, before she was nominated for a Tony Award and then, of course, before she could attend the Tony Award ceremony and see Raisin win the top prize.

Tiny scraps of information—I still had so many questions about her life. Then, last year, Raisin was announced for the Astoria Performing Arts Center season, directed by the artistic director Dev Bondarin. Raisin had not had a production in New York City since 1981 at the now defunct Equity Library Theatre. My quest suddenly had more urgency.

I visited the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center for clues. All I found, however, was her bio in the Raisin Playbill, published after her death, and a book of collected Raisin reviews, which cemented how important her contribution was to the show. Praise for the show’s book was front and center in the majority of reviews—no small feat, as the book is often the element of the show hardest to get right and is usually the most critiqued.

Clive Barnes wrote in The New York Times in October, 1973: “The present book by Robert Nemiroff and Charlotte Zaltzberg is perhaps even better than the play. It retains all of Miss Hansberry’s finest dramatic encounters with the dialogue, as cutting and as honest as ever, intact. But the shaping of the piece is slightly firmer and better.” He went on: “In a sense the score (music by Judd Wolden and lyrics by Robert Brittan) for Raisin is not the most important aspect of the show…. You hardly notice this—or at least you only notice it in passing—not only because of the exceptionally superior book, but also the enormous strength of the staging and the performance.”

A woman had co-written a book that even The New York Times had singled out for praise and yet the question remained: Who was Charlotte Zaltzberg?

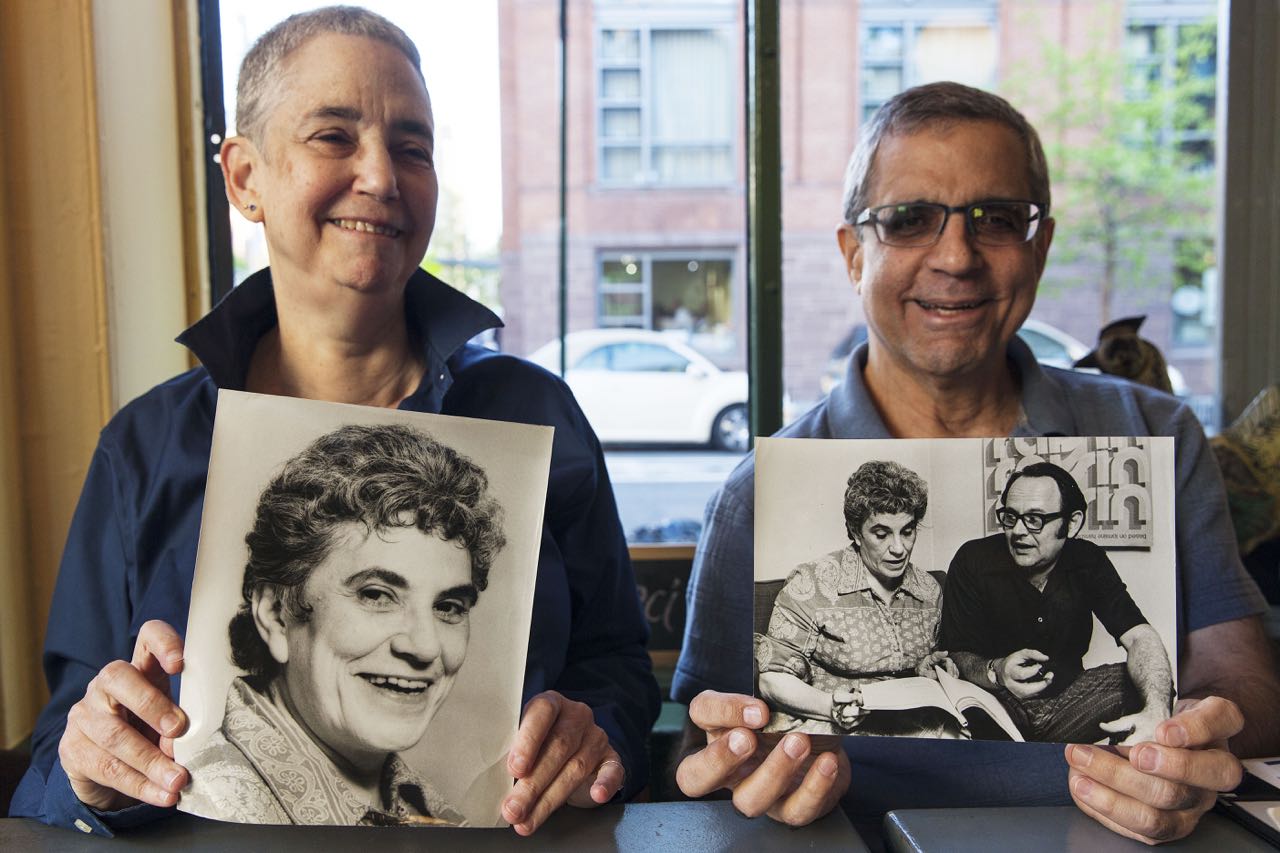

Finally, after I spoke to Bondarin about her production at APAC, running this month through the 27th, I was able to find Zaltzberg’s children through names written on the Raisin script. Ellen and Harry graciously sat down with me to share memories of their mother and examine old photos and Raisin memorabilia.

Charlotte Zaltzberg was born Charlotte Singer in The Bronx, New York in 1924, the youngest of six children. Her parents were from Poland and then settled in the Bronx. Her mother, Ida, spoke very little English; her father Harry worked in a jewelry shop on Hester Street. Zaltzberg was closest to her sister Sadie, who was eight or nine years older. Sadie took young Charlotte under her wing and, with her future husband Joe, took her to the theater.

Sadie’s husband-to-be Joe was none other than the future Broadway bookwriter Joseph Stein, known for his book for Fiddler on the Roof, as well as the musicals Rags, Zorba, and Juno. Stein adored Zaltzberg, and his theatrical influence would have a lasting effect. At some point in the writing process of Fiddler, which opened on Broadway in 1964, Stein sent her the script for her input. “He trusted her and had some sense, even back then, about her judgement,” Harry said. “I can still visualize the script sitting in our den.”

Another influence for Zaltzberg was her political upbringing. She went to Jewish socially progressive or “lefty” summer camps such as Camp Unity in Wingdale, New York, a few hours north of the city. Camp Unity had a rich cultural program as well, which brought in jazz musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie. The summer camps fueled her young activism, and in high school she was in the American Student Union, a national left-wing organization usually for college students. Her early organizing also included fundraising and working for unions after attending Evander Childs High School in the Bronx.

In 1947 or 1948 she married Alex Zaltzberg, a social worker who had been badly injured in World War II during the Battle of the Bulge. They were active together in progressive, civil rights work. Ellen was born in 1949, Harry in 1953, and they lived in West Harlem before moving into one of the new projects for veterans in Marble Hill. In 1957, they moved out of the city to Croton, New York, up the Hudson River.

Croton was home to many left-wing artists, including folk singer and songwriter Lee Hayes and Hansberry and Nemiroff. The 1960s saw the rise of civil rights actions across the country, and the residents of Croton went to nearby Ossining to picket the Woolworths after four black students were refused service at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, a Woolworth’s store. Later, the local rabbi held a rally and fundraiser for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and Hansberry spoke.

Protests and marches were commonplace in the Zaltzberg household. Zaltzberg brought her young daughter to the Woolworth protest and in 1963 to the March on Washington. Ellen recalled another anti-war demonstration in DC in 1971 with Sadie and her sister-in-law Ruth. Zaltzberg would leave for the demonstrations at three thirty or four in the morning and travel down by bus.

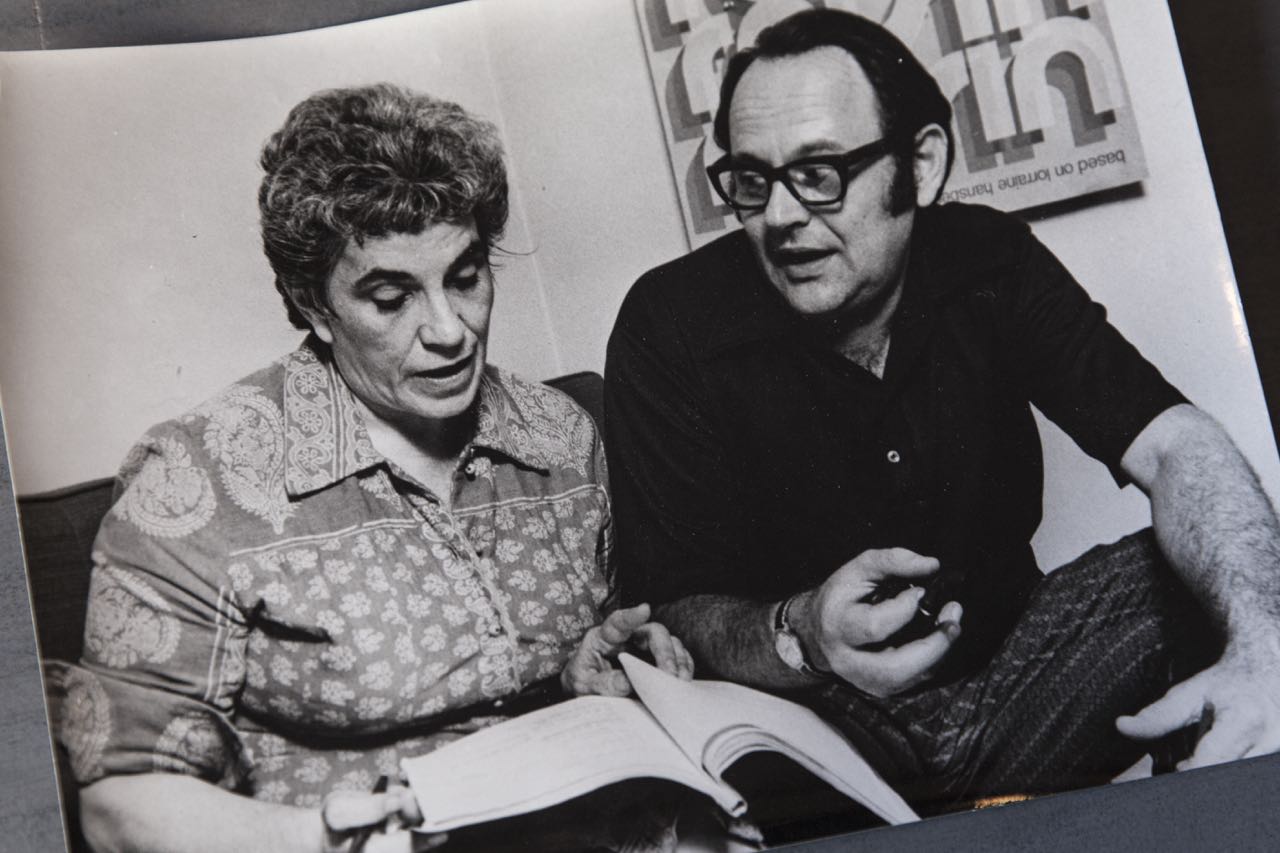

After Hansberry died in 1965, Nemiroff became the executor of her estate and soon needed a secretary. Zaltzberg was hired the following year, and after a short time proved to be much more than a secretary. She assisted in organizing Hansberry’s archive and wasn’t one to hold back thoughts and opinions.

Zaltzberg’s first major project with Nemiroff was helping to adapt Hansberry’s writings for a WBAI radio documentary, To Be Young, Gifted and Black, which aired in 1967. They then adapted Hansberry’s writing into the play To Be Young, Gifted and Black. The play received good reviews when it ran off-Broadway in 1969, and a subsequent tour went into the south and to all-black schools. Zaltzberg herself adapted the one-woman version. The title comes from a speech Hansberry gave shortly before her death.

In 1970, Zaltzberg worked with Nemiroff to bring Hansberry’s last play, Les Blancs, to Broadway. She was billed as the script associate and worked with Nemiroff to finish the play, using incomplete drafts. The play was heavily criticized and closed after 40 performances but it received two Tony Award nominations for Best Costume Design and Best Featured Actress. It also won a Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Performance for James Earl Jones.

During this time, perhaps when there were lulls in the work, Zaltzberg worked as the general manager of the Mayfair Theatre, a Yiddish theatre company in the Mayfair Hotel in midtown. Since Zaltzberg knew Yiddish, she worked to bring in audiences from the surrounding areas such as Long Island and New Jersey, a job she loved. Ellen and Harry said that for Zaltzberg, working there was “like going back home.”

Zaltzberg was funny. She ended one of her Raisin bios with the line: “Ms. Zaltzberg has been racing to complete her play script on ‘modern marriage’ before the subject becomes obsolete!”—she had separated from her husband in 1969. She played the piano by ear and sang, and she loved to dance. One of her greatest loves, of course, was the theatre. Her skill in writing was in adaptation and bookwriting, just like Stein. In another one of her bios, she wrote that she “did not formally think of herself as a writer until very recently, although between responsibilities as a secretary, housewife and mother she had, like many gifted women, filled literally thousands of pages over the years with sketches, stories, poetry and writings of all kinds.” Aside from Stein, Zaltzberg was influenced by the writer Sean O’Casey. She read poetry, such as Shakespeare, Millay, Dickinson, and Yeats, and loved the Group Theatre, Paul Robeson, and Mark Blitzstein.

The musical version of A Raisin in the Sun had a long gestation period. Soon after Hansberry died, Nemiroff chose a treatment from composer Judd Wolden and lyricist Robert Brittan. An article in an April, 1974 Jet Magazine quotes him as saying, “[They] brought me a spectacular adaptation of the play, and immediately I was impressed with their love for the material and their serious attempt to really dig down to the roots of the play.” It then took seven years to get the interest and backing from producers, who, like those who looked at A Raisin in the Sun decades earlier, believed in the work but didn’t think it would sell.

The musical finally had its pre-Broadway opening at D.C.’s Arena Stage in April of 1973, where it ran two months over its one month scheduled run. It was during that time that Zaltzberg was diagnosed with inoperable breast cancer. There was nothing the doctors could do, but she came back to work and continued writing.

After another successful pre-Broadway tryout in Philadelphia, the show opened on Broadway that October. At that point, Zaltzberg’s sister Sadie was also very ill, but they both attended the opening night. Zaltzberg’s health declined immediately after the opening. She had held on long enough to complete her work and died on February 24th of the following year. Sadie died that April.

The Raisin family—cast, crew, producers—participated in a memorial for her. The cast sang songs from the show, including the song “Measure the Valleys,” the song that the character Mrs. Younger sings about caring about people when they are down.

After her death, Nemiroff wrote a letter to investors that went over some odds and ends. At the end of the letter, he informed those who were not aware that Zaltzberg had passed away. He wrote: “She was a woman of enormous talent and unfailing zest, with a rare and extraordinary competence appreciated by all who knew and loved her. There is a void that cannot be filled, but we will carry on in the tradition of unflagging spirit which Charlotte reflected. To Be Young, Gifted and Black; Sidney Brustein; Les Blancs: and now Raisin—to all of which she gave her creativity—are monuments to that spirit.”

How does one ensure that a theatre artist’s accomplishments remain known? Today, one needs an Internet presence, but what about 50 years from now? It’s up to everyone to gather the information and make it accessible in the popular format of the day. We must also keep producing their plays and musicals.

“If the work doesn’t get seen and heard, it’s hard to create that legacy,” Bondarin said. “The more women get those chances, the more the work is seen and heard. The fact that Raisin has a female co-book writer [Zaltzberg] and that the musical is based on Lorraine Hansberry’s play is a significant thing.”

We don’t know what would have been possible if Zaltzberg had lived beyond her first Broadway success, but her contribution to the work, to Hansberry’s own legacy, and to the American theatre is important. And so is her story.