Lynn Nottage on the Music and Images of Writing “Sweat”

Written by Victoria Myers

Photography by Violet Overn and Stephanie Gould (courtesy of Lynn Nottage)

Playlist courtesy of Lynn Nottage

December 6th, 2016

Last October, while being interviewed for The Interval, Lynn Nottage stated that people often act as though a play of hers “just spontaneously writes itself, not understanding that there’s a great deal of thought and craftsmanship that goes into the creation of the work.” That sentiment has been echoed by many female playwrights. We thought it would be interesting to show some of her craft in writing the critically acclaimed Sweat, a play about factory workers in Reading, Pennsylvania that is now playing at The Public Theater and will be opening on Broadway this spring. We asked her to share with us the playlist she made while writing the play and the visual images she took on trips to Reading. Over the phone, we discussed how she used the music and images as part of her writing process, her opinions on the differences between journalism and playwriting, and how the creative process can get lost in the conversations surrounding political plays.

Where did you start in terms of gathering the music? As I recall, when we spoke last year, you mentioned that some of the songs were a little outside of the things you would normally listen to.

Yes, that is definitely true. It was an adventure just to find music that I felt captured the mood and the ambiance of Reading, and it was purely subjective, because I didn’t know the music that folks were listening to. Certainly when I played the music, it conjured Reading for me, and conjured the mood of the play that I wanted. That’s why if you listen to the playlist, there’s some electronica, there’s some R&B, there’s some rap, there’s some alt rock. Most of it is upbeat, because I saw the play as being rhythmically upbeat. A lot of the music is driving, and so the play has this engine that’s sort of turning forward, and the music helped keep me in that place. When I felt like slowing down, I would put the music on and immediately my heart rate would elevate.

Did you have songs for specific characters?

Yeah, I certainly had songs that I felt reflected the rhythm of certain characters, and so I played those songs when I was writing them.

Were you part of choosing who was photographed?

No, in the case of the photographs, there were individuals that caught the photographers’ eyes. There are two sets of photographs: the ones that are sort of formal portraits, which are against the wall, and [the ones by] Violet, who is an intern, of people that she interviewed.

When you’re writing, do you picture the physicality of the character?

I have a mind’s eye notion of what they look like and how they move, and often that’s slightly shifted when we cast, but I definitely have a real firm sense of what my characters look like. What’s interesting is when I write plays, in my head the play is absolutely complete, but I’m not always interested in that version of the play when I’m done, I’m interested in the collaborative version. For this particular play, physically, it was less important what people looked like and more important what energy they brought to the role.

Did you find any particular challenges in terms of creating the world of this play, because it is something that is both so close, and one that people might see as being very far?

I spent so much time in Reading, and it didn’t feel far away after a while. The characters didn’t at all feel foreign to me, so I don’t think that I struggled when I was putting them onto the page because I had a familiarity with them. They’re people that we all know. They’re people that live two doors down from us, who we may not take the time to talk to. That was not one of my struggles. Whenever I enter into a play, I always imagine the characters are people who I know.

Do you do quick first drafts, or slow?

Well, in the case of Sweat, I developed it at the Lark [Play Development Center], so I was bringing in a new scene once a week. By the time the workshop was over, I had an almost finished play. In that case, I think that it came more quickly than it usually does because I had this organizing principle. Each play is different. Fabulation was written very quickly, like in one exhale. Other plays have taken longer. For instance, with [By the Way, Meet] Vera Stark I wrote the first act very quickly, and then put it away, and then two years later came [back to it] and wrote the second act.

Do you find that also has changed with age and experience?

I do. I think that I have much more control of my craft, and that I can get to a first draft more quickly than I could when I was younger. I also think that I don’t have to rewrite as much because I am able to incorporate that rewriting into my initial writing in ways that I don’t think that I could have when I was a young writer.

When you were working on Sweat at the Lark and bringing in chunks by scene, was there anything about that that you ever found frustrating? Especially as it related to it becoming a whole play?

I always find the process of bringing in fragments of a play a curious process, just because you’re inviting people to respond to something out of context—I thought that that was interesting—and to hear feedback prematurely, which is something that I generally don’t tend to like. But I felt that it sort of drove me forward. I wanted to get to the end because I wanted people to see the work in context.

Did you find that that affected the structure at all?

I’m sure it did. I have to look back and sort of examine how it affected structure, but I have no doubt that it affected the way I started out the play. In part because I knew that I was bringing these little bite-sized morsels that needed to feel slightly more complete than usual, because people were going to be reading them aloud. I was very conscious of bringing in work that could be read.

We talked a little bit about this before, but to you, what is the difference between a playwright interviewing somebody and a journalist interviewing somebody?

The way that I would describe it is it’s a completely different process because I think that a lot of times the journalist going in has a sense of the story that they want to write. I can hear it even in questions that you ask, or other people ask—I can hear me being led somewhere, as opposed to, as a playwright, a lot of times I’ll ask questions and sit back and listen. I probably spend a lot less time interjecting and a lot more time allowing people to have a stream of consciousness as they’re speaking, because I’m really interested in the stories that are unprompted. The stories that sort of rise to the surface when they have certain emotions. Also, the other thing that I think is a little different, is I went to Reading quite often, so over the course of time I got to know people, and the nature of our relationship shifted and the nature of our conversations shifted as I got to know them.

Then, of course, when you sit down to write, it’s a totally different process.

Well, yeah, but also when I’m sitting down to write I’m not writing what I experienced verbatim, I’m using what I heard to inspire characters who are purely fictional. I think that on some level they know that, that I’m not poaching their lives. I’m just sort of drawing inspiration from their lives.

Part of why I was so interested in doing this piece with the playlist and the visuals, is because it seems like with work that is described as political, sometimes people forget to acknowledge the creative process that goes into it.

Well, I think for so long that political was a bad word when it was attached to theatre, which always was incredibly curious to me. One of the reasons I go to theatre is to be stimulated, to be challenged, for questions I hadn’t considered asking. I think that so often critics are dismissive of plays about things other than the comfort of your couch and sort of the quandary of your feelings. If they go into a theatre and they actually feel slightly challenged, I think that it’s seen as an irritation. They tend to move away, which I find fascinating.

When doing press for Sweat, is there a question that you wished you had been asked that you haven’t?

Yeah. I feel like so often, as a woman, I never get asked craft questions. We talked about this, and it remains true. I’m always asked about the politics of the play, but never about the craft of the play, which sort of points to the question that you asked with regards to the political plays not seen as being crafted. No one asks me about the structure of the play.

Do you feel like that’s been especially true with this play?

I do. I think it’s interesting. It was true with Ruined as well, because of the timing of that play. I tend to write plays that engage with culture and they’re in conversation with the culture, so a lot of times people think, “Oh, they’re just written.” They don’t think about the research that went into it, and the consideration, and the fact that I thought about this play for years before it came to fruition. I’ve been mulling over the ideas for some time. Also, the notion is that I didn’t consider what was happening politically when I was writing it. Absolutely I was considering politically what was happening, and it’s part of why we wanted the play to be produced just before the election. I knew exactly.

Lynn Nottage’s Sweat Playlist

Smooth – Santana

Big Pimpin’ – Jay-Z

107 degrees – Citizen Cope

When a Woman’s Fed Up (radio version) – R. Kelly

Teardrop – Massive Attack

American Woman – Lenny Kravitz

The Real Slim Shady – Enimem

Maria Maria – Santana

Salvation – Citizen Cope

Fly Away – Lenny Kravitz

No More Drama – Mary J. Blige

Just Fine – Mary J. Blige

Bullet and a Target – Citizen Cope

Little Black Submarine – Black Keys

Live With Me – Massive Attack

Everything Is Everything – Lauryn Hill

You can listen to Lynn’s playlist on Spotify by clicking here.

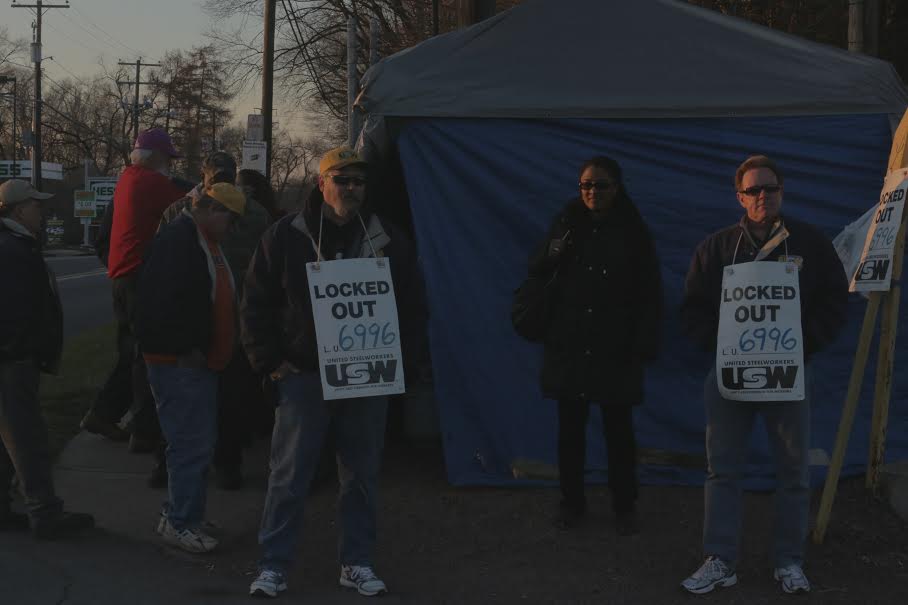

Photos from Reading, Pennsylvania