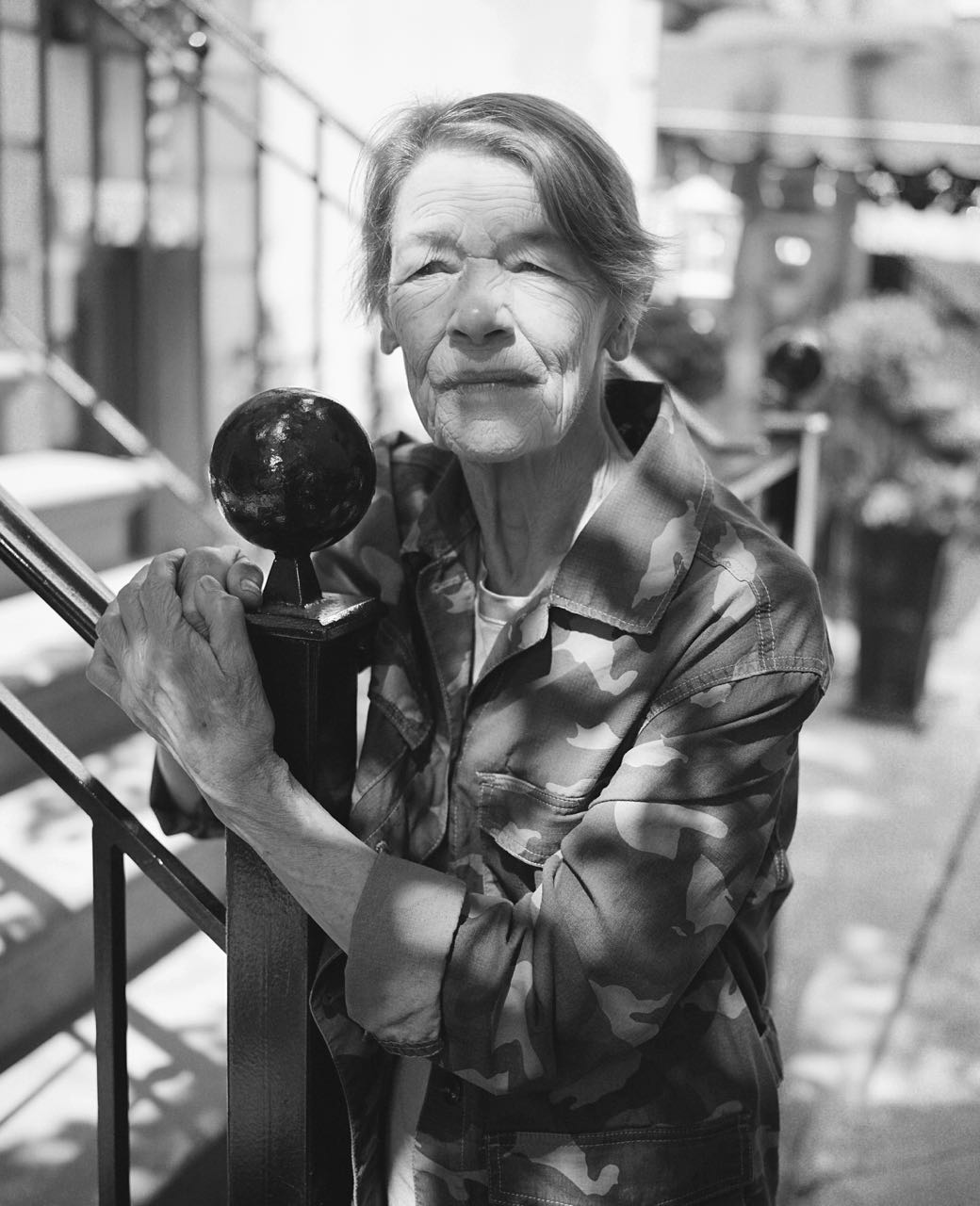

An Interview with Glenda Jackson

Written by Victoria Myers

Photography by Marisa Chafetz

June 5th, 2018

The Friday I interviewed Glenda Jackson over tea was the Friday I was supposed to be having a root canal, which I was prepared to bring up as I’d recently read an article titled, “My Disastrous Tea with Glenda Jackson,” in which Jackson was described as cantankerous and obtuse. I was also prepared, depending on how the conversation went, to bring up that one time Nicki Minaj had fallen asleep (multiple times!) during an interview with Taffy Brodesser-Akner, and that it had still turned into a perfectly delightful profile. Of course, 90% of interviewing anyone is just getting out of the way, letting the other person talk, and then writing accurately about it. So when Glenda Jackson and I did sit down at Alice’s Tea Cup, there wasn’t much need to make a joke about root canals or Nicki Minaj, since all that happened was I asked her some questions and she answered them while all the tables in earshot listened, including one with a mother and daughter where the mother was very excited that her daughter, an aspiring actress, got to have tea adjacent to multiple Academy Award-winner and former UK parliamentarian Glenda Jackson. We spoke about her current Tony-nominated performance in the revival of Three Tall Women, her career in acting and politics, and her views on both. Minus the tea, which neither of us actually ordered, this is about how it went.

Do you think people—audience, critics, whoever—approach revivals too much like there is a right way to do them or a fixed way to do them, instead of seeing them as living things?

It’s never occurred to me. I’ve never been aware of anybody bringing that thought to the production because it’s a revival. They may bring that sort of thought because they don’t like it, but I don’t think it’s necessarily that they’re making time comparisons.

It might be an American thing, seeing theatre like literature, in the sense that they saw it as much more fixed.

Again, that hasn’t been my experience. For example, I did Strange Interlude here, which is an American classic and you can certainly put O’Neill in the kind of literature box, but that was never an issue that was raised. We may have, all of us, have fantasies about our own knowledge. We think we know things when in fact we don’t.

There have been a lot of conversations recently about why to do a particular show during this time period. In terms of Three Tall Women, is that something that you thought about?

I didn’t even know it existed until I was sent the script. Obviously, it’s an extremely good, extremely interesting play, but also one of the other big things for me was the opportunity to work with other actresses, because usually there’s only one woman’s part, and if you’ve got it you’re not working with actresses. That, and actresses of this caliber, is just such a privilege, really.

That’s something I wanted to ask you about because I heard you say that in other interviews. Looking back over the scope of your career, and also looking forward, what do you think the state is for parts for women in theatre?

It’s exactly the same: minimal. I’m talking about contemporary dramatists obviously, but I see no major move in contemporary dramatists finding women interesting. They don’t. We’re rarely, if ever, the dramatic engine of their plays.

Why do you think that is?

I wish I knew, because if I knew then perhaps I could tell them and perhaps they’d begin to think differently, but I don’t know why it is. It may not be that it’s exclusively in the realm of what dramatists find interesting. I think there may be, still, a sense that the entire industry has reluctance to acknowledge [women’s stories]. Well, that isn’t true, because it does become a big deal, for example when a film is up for an Oscar and is directed by a woman. But I think that’s pretty much true. I don’t really see any fundamental change in as much as, to put it in a cliché box, if a woman is successful, she’s deemed to be the exception that proves the rule. If a woman fails, it’s simply proved we all can’t do it, and that doesn’t seem to me to be shifting at all, in any area.

Thinking back, 30 years ago, did you think things would be different by now?

No, I think I may have hoped. I still hope, but the reality is that there’s seemed to be no change at all, really.

I want to talk a little about acting first. People label acting as an interpretive art. Do you see it as being strictly interpretive or do you also see it as being generative?

Certainly the latter, because you have to view the world through the character’s eyes. You can’t judge them. That is part of digging out the energy of the play. It’s all in the text, actually. You can build up backstories which help you, but that’s essentially what it’s about. Having said that, of course, another way of looking at it, which is a way I do, we are put down in the middle of a jungle with no compass or map or anything. We know what it is we’re wanting to find, because everybody’s responsible for the whole play, but of course, for the dramatist, who is the creator, that sheet of paper stretches to infinity. In one sense, we have borders, but it’s what we find within those borders that I think is what we bring to it.

When you’re working on a play, do you think of it as a play, as something that is constructed and structured, or do you try to think of it as close to life as possible?

Oh, no, because you don’t do it on your own. I had the script, but I didn’t have the cues. I didn’t have the other voices. I didn’t have the other words, and that’s part and parcel of what you’re trying to do. You learn, essentially, to forget, so you can listen.

Do you also then think of the characters as being a construct rather than being real?

What’s reality? Tell me, what’s reality? We’re talking about an art form which takes as a given that the other participants of the evening suspend disbelief. So what is real?

What do you think people get wrong when they talk about acting?

I think they tend to regard it as though it’s a game, it’s fun, it’s sort of play. It isn’t. It’s extremely hard work.

What do you feel like has been the most positive and the most negative change that you feel like you’ve seen in the theatre in the course of your career?

I think the issue of the continuing dearth of parts for women in contemporary dramas has come more to the forefront. I don’t necessarily think it’s sort of racing ahead and that people are actually rethinking it, but I hope that it will happen. The age issue hasn’t changed at all. It’s still all pretty much as it was. In many instances, the purpose of having a woman in the play is her attractiveness or lack of attractiveness, and then you get to the stage where they’re there because they’re old and they’re a kind of cliché about what it is to be old, or what people are capable of doing and being.

One of the things that I ask actresses a lot is how, when you are in an industry that’s so into typecasting and making a lot of pronouncements about who you are, what you’re good at, what you’re not good at, what people see when they look at you, how does that affect how you develop as both a person and an artistic person? Do you feel like stuff like that had an effect on you?

I didn’t really approach it from the aspect. When I became a member of parliament someone said to me, “How will you manage working in what is essentially a man’s club?” I said, “But that’s been my experience all my life.” We are seeing cracks in that area, but we are still, as I said to you earlier, deemed to be successes that are the exception that proves the rule or we are failures, which means we’re all useless.

When you came back to acting after being in politics for so many years, did you find that that had changed your approach to it or how you thought about it?

No. It was as though I’d never been away. It was quite astonishing. A friend of mine said, because I’d been moaning about, “Oh, I don’t think I can do it anymore,” and she said, “It’s like riding a bicycle, you never forget.” I said, “I think it’s rather more complicated than riding a bicycle.” In the theatre, everyone engaged in the production is responsible for the whole play, and that does create a kind of unity of purpose quite apart from anything else, and you’re all just part of that, and that doesn’t change. That is always, always very warming to be part of.

Did being in politics change how you viewed the theatre as an institution?

No, because certainly at the moment, and when I was first elected, money being the bottom line [was a big issue]. The battles to keep money going into the arts and for the cultural life of the country is always very difficult because it’s always deemed to be just fluff, and so it can be discarded when the budgets have to be tightened, and that hasn’t changed, either, which is a bit depressing.

This may be connected to the lack of progress in terms of women in theatre, but what do you feel like is the biggest lie that the theatre community tells about itself?

I don’t think, at its best, it does tell lies. Those are the two things that I find interesting about my two careers. The best theatre tries to tell the truth about what we are as people. The best politics try to do that, too, in the hope that a society can be created in which the undoubted unique individuality of everybody on this planet is allowed to flourish without sabotaging anybody else’s flourishing.

Do you think if you were a man, you would be talked about differently in the press?

Oh, of course, of course. The age wouldn’t matter, what he was wearing wouldn’t matter. They’re the first things that people talk about. Two things that have always amazed me is when reporters or people say I’m frightening. I never understand why. The other is that I speak in complete sentences. I don’t know what that means.

It seems like recently there have been more conversations about women in the workplace. Did you feel, early in your career, that there was ever a sense of isolation in terms of things that you were dealing with?

Of course there’s a sense of isolation. You don’t get work. That’s the prevailing desire when you first enter the theatre: to have a job, to be acting. They’re very few and far between and the gaps between employment can be very long. For instance, I didn’t work in the theatre for two years and thought, well, that’s it. It’s given up on you.

When you start out, you’re not in any position to pick and choose. Just to get a job is the essential thing. I, for example, never ever got a job from an audition. You can spend several days readying yourself for an audition. I know it’s changed now. But you would go into the room and there would be people sitting behind a table and they’d look up, see you, and say, “Oh, sorry darling, we want a blonde,” or, “Sorry, dear, we’re looking for a brunette,” or, “You’re too tall,” or whatever. That was it. It’s not a personal rejection, but it’s very hard to realize that it takes time.

I would think that would be very hard to not take personally.

It is very hard to not take personally, but it isn’t personal. That’s just the rules of the game.

Was that an attitude that you had to come to?

It’s not an attitude you have to come to. It’s the experience teaches you, but the first time it happened, more than just a first time, it’s very, very painful.

Going along with that, being in environments that are male-dominated, we hear a lot of stories, and not even getting into the very bad things about women being spoken over and not taken seriously. Did you feel like you experienced a lot of that early in your career?

No, because there was still the hierarchy of the size of the part, and I always had very small parts. But certainly, it was blatantly obvious when I entered parliament. But what was interesting about that time was, even though we were by no means the majority in parliament, there were more women MPs, and so there would be more than one woman sitting at a committee table or something like that. An example: I was in the committee, and one of my colleagues put up an idea, the chair committee said, “Oh, yes, that’s fine, thank you,” moved briskly on. A few moments later one of the men put forward the same idea and the chair said, “Oh, that’s marvelous.” Everybody was very marvelous, and another of my colleagues who was sitting said, “But she said that 10 minutes ago,” and a little hush all around the table. We did start speaking up, but of course, the minute you do that, you are automatically deemed to be a ball breaker or something of that nature.

Did you feel like you changed at all when you entered politics?

Well, hopefully, life changes your view of the world. It’s a very humbling experience, being a member of parliament, because your constituents come to you, and not infrequently. Their lives are dreadful, usually through no fault of their own, and they come to you because you’re the port of last resort. You may not always solve the situation for them, but you can get an answer to a letter, and you can get people who will respond to your phone call. Invariably, the individual says thank you, and that’s a very humbling experience. In that sense, yes.

What was the hardest thing about sustaining a career in politics?

I never thought of it as a career. I was never looking to go up the greasy pole. Certainly, I wanted to be reelected. I wanted to remain a member of parliament by constituents because it was my constituency that was a major concern to me. There were things I wanted to see improved. Certainly, when we as a party came into government, the issues that were of primary importance in my constituency were the issues that my government wanted to tackle. I didn’t regard it as a career in that sense. It was to do the work as well as I could, and obviously, when the elections were called, to be reelected.

What do you feel has been the most challenging thing about maintaining your acting career?

Getting work. It’s just having a job, just getting work. Every time you finish a job you think you’ll never, ever work again, and that is pretty much, I think, what most actors feel. It sort of goes with the territory. That’s the way it is.

Do you consider yourself ambitious?

I want to find the play. I’m ambitious for that, and I’ve been really lucky in that I seem almost invariably to work. As I said earlier, there is a simple goal that we’re all wanting to reach, and we accept the responsibility for the whole play.

Do you feel like ambition, like some of the other things that we’ve been talking about, can be complicated in terms of how women are viewed?

It depends what they’re ambitious for. Where does the ambition lead? What is their ambition driving them towards? Where I think there are pratfalls is when people accept other people’s definitions of what they should be as women. I think that’s very, very hard to weather, to ride, particularly I think for young women, when they’re told what they should look like, what they should sound like, what they should be.

I would think that would be tenfold in the acting profession, in terms of having people tell you how you should sound, how you should look, and what that does for you.

Who tells you how to sound and how to look?

Casting directors, directors, producers.

Not if they’re good, because everybody is hoping to find the play. That’s what everybody’s engaged in doing. You still come up against the big barrier which is an insufficient number of writers who find women interesting, and therefore, the inordinate variety of women is never explored. We’re always deemed to be some kind of homogenous group and that’s why plays that don’t look upon us like that are so rare and so wonderful to do.

Do you have a spiritual life, and if you do, do you feel it affects your work?

Define spiritual. If you’re asking me do I have a religion, not one that I practice, but I certainly believe we as human beings are more than flesh and blood. There are dimensions to it, and very often we don’t know we’re there until some incident, something happens, and we’re aware of it. It is something that I value and certainly one of the things that I was so exercised about during Thatcher’s reign was the kind of spiritual dearth in my country. I don’t mean that people didn’t go to church or things like that, but that the country, too, as a kind of spiritual dimension, seemed to just be something that was kicked into the rubbish bin.

Do you feel that that affects your work?

Everything affects your work, everything. You may not be aware of it at the time, but hopefully you’re like a sponge.

What do you feel people get wrong about you?

They think I am the characters I play, but of course I’m not. I’m very boring. I lead a very ordinary, dull life. The choices I make are mine. I am a big disappointment to people, there is no question, because they expect me to be what I play, but I’m not.

Over the course of your career, did you ever feel as an actor that you had any power to say, “No, I don’t want to be treated this way,” or, “I don’t think somebody else should be treated that way,” or, “I would like there to be more women on the creative team”?

It isn’t like that. That isn’t what a rehearsal room is like. People in the rehearsal room, firstly, they’re always grateful because they’re being employed. You don’t have to like people to be able to work well, because what you’re aiming to do, you’re all sharing in that. No one’s given you a box with all the bits in it. You have to find it and you have to make it true. Obviously, if someone is actually being vicious to another actor in front of all the other actors, well, I’ve never experienced it, but I would hope people would stand up and say, “Hang on a minute,” but that’s not the basic structure of the work we’re doing. The basic structure is: are we in work or are we not, and that’s the big thing.

How do you balance that then, the structure of your work, with going back to what you’re saying about writers not finding women interesting? I would think an option could be to be like, “If you want me for this, I want there to be fully fleshed out female characters. I want there to be women on the creative team.”

Oh, come on. Then why have actors? You make it sound as though we’re just dummies that can be put on the stage. What do we bring, if that’s all we’re asking for, if that’s all that’s demanded of us?

If you’re asking for more women on the creative team?

No, you’re saying that, why are we not saying to a creative writer, “You should do this for me or for us.” That’s ridiculous. Why have us, then? You can get dummies to do that.

Do you feel that connects to what we were talking about earlier of acting as being not just interpretive then?

There’s a difference between interpreting and creating, isn’t there? They’re not the same thing. What I’m saying to you is that there is, I suppose, like a secret, really, but you always hope you’ll find it. There is an energy in the play and it’s the work that you do together that hopefully finds that energy which transforms and brings something to the play, which isn’t there when you just read it. Once you’re performing, once the play is on, once you’ve felt that energy, you shouldn’t have anything to take home. Everything you do should happen on that stage. One of the things which I don’t think the people who watch theatre or even produce it or write plays are aware of is that every performance is the first performance. I don’t care what they call the night the critics are in, every performance is the first performance, and you shouldn’t have anything to take home. The important thing is what happens between the area that is lit and the area that is dark, the connection between those two.

Do you think about your legacy at all?

Never. What legacy?

As an artist, as a politician, as a person?

Oh no, I’ve never been thought of as an artist, because as I’ve said, every performance in the theatre’s the first time you do it and there’s no record of that other than what an audience, I suppose, takes away. With regard to politics, I would think if there is anything it would be very, very small and it would be on a, I think, possibly very personal level.