Lillian Hellman’s Regina Giddens: The Theatre’s Original “Nasty Woman”

Written by Sarah Rebell

Graphics by Desiree Nasim

June 19th, 2017

When I set out to write a piece on The Little Foxes, I headed right to the Drama Book Shop in New York City, to browse and research all things Lillian Hellman. Shockingly, there were no biographies of her in stock or on order. She was not even included in the Drama Book Shop’s most basic book series outlining the lives of accomplished American playwrights. I perused Barnes and Noble and independent bookstores with large theatre sections, but all to no avail. The most recent Hellman biography (less than five years old and provocatively titled A Difficult Woman) was even hard to obtain on Amazon; I had to purchase it through a third party seller. Not only are Hellman biographies in short supply, so too are Hellman revivals. Her plays have only been brought back to Broadway six times total, as opposed to the 25 Broadway revivals for Arthur Miller, or the 31 Broadway revivals for Tennessee Williams. To this day, she has never won a Best Play or Best Revival of a Play Tony Award. The sixth and current Hellman revival is of her most acclaimed play, The Little Foxes, which is about the unconventional Southern matriarch Regina Giddens, who manipulates her brothers’ moneymaking scheme with grit, ambition, and business acumen.

Of course, Hellman was a fairly unconventional woman herself. Born into a Southern Jewish family, Hellman was, as a woman and a Jew, automatically placed in the periphery of society, twice over. Nevertheless, she grew up to become a popular playwright, spinning successful stories depicting strong women. Independent and outspoken, at the time of her first Broadway hit she was a divorcée engaged in a fairly public love affair with a married man. Hellman was even blacklisted in the McCarthy Era for refusing to cooperate with the HUAC, instead famously claiming, “I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.” But these things were part of her notoriety and celebrity appeal, not the cause of her downfall. Despite her apparently unladylike lifestyle, Hellman was adored throughout the middle of the 20th Century. Her reputation only became irreversibly tarnished in the 1970s, when a fellow female writer accused her of plagiarism. By the time of her death in 1984, this once celebrated woman has fallen into a state of semi-obscurity in comparison to her contemporaries.

A recent New York Times article by Jason Zinoman (in response to an article by Washington Post critic Peter Marks) questioned whether Hellman actually belonged in “the same elite club of 20th-century masters” as Miller and Williams. Zinoman concluded that Manhattan Theatre Club’s current revival of Foxes would be an opportunity for the piece to prove itself. (He neglected to mention that this MTC production is the only revival of play on Broadway this season that was written by a woman. Furthermore, it is the first time a woman has produced this play on Broadway; a woman has still never directed it.) It is absurd to think that nearly 80 years after Foxes debuted, the play is still fighting to prove its worth. For the record, reviews of the MTC revival from The Washington Post, Variety, and The Hollywood Reporter described Foxes as “worthy of exalted rank in the American canon,” “astonishingly well-constructed,” and “too seldom revived on Broadway,” respectively. Even The New York Times review—albeit not by Zinoman—conceded that Foxes certainly “comes pretty close” to deserving “a place in the first rank of American theater.”

Curious to know how earlier productions of Foxes had been received by theatrical critics, I downloaded some reviews from The New York Times archives. Three Broadway revivals ago, a 1981 article by Frank Rich described Regina, the tour-de-force protagonist of Foxes, as a “malignant southern bitch-goddess.” The same paper that refused to print the full title of the play The Motherfucker with the Hat in 2011 had no problem printing the word “bitch” thirty years earlier. These days, the word “bitch” is used fairly causally (and it is certainly not likely to be considered as potentially offensive as “motherfucker”), but it is still a derogative, gendered word for which there is no male equivalent. “Motherfucker” might well be the next closest thing.

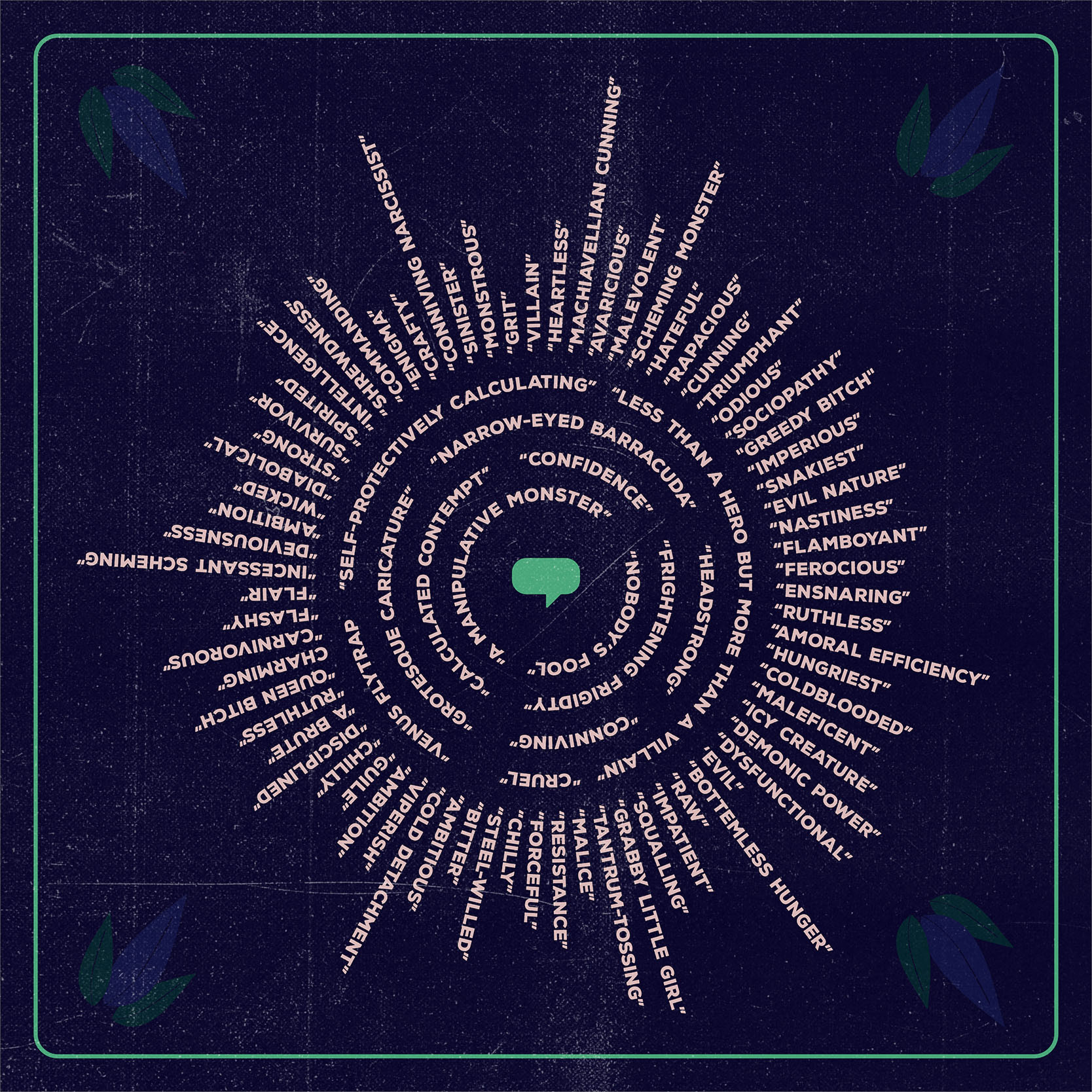

A 2014 article by Justin Peters on the Times’ “profanity policy” quoted Standards Editor Philip B. Corbett, who explained that Times writers “are prepared to make exceptions if the use of a vulgarity is newsworthy or essential to the story, or if avoiding it would deprive readers of crucial information.” The position of standards editor had not yet been created at the Times when Frank Rich published his 1981 review, but the profanity policy was based on rules from the paper’s style guide at the time. Was it “essential” to refer to Regina as a “bitch”? Would readers have been “deprived crucial information” if another word had been used instead? Not likely, considering that Brooks Atkinson managed to review the original production for the Times back in 1939 without resorting to profanity (although the character of Regina was described there as “heartless,” “ambitious,” “avaricious,” “malevolent,” “calculating,” “hateful,” “rapacious,” “cunning,” and “odious.” Synonyms for bitch, perhaps?).

Just as there is no male equivalent for “bitch,” there seems to have historically been no real equivalent critical response to similarly strong, complex female characters in plays by the men who made up Zinoman’s “elite club of 20th-century masters.” In the Times’ 1945 review of the original Glass Menagerie, critic Lewis Nichols is almost an apologist for Amanda, to whom he frequently refers not by name but as “The Mother.” He sympathetically describes her as “a blowsy, impoverished woman living on memories,” and “trying to do the best she can for her children.” Brooks Atkinson’s Times review of the original 1947 A Streetcar Named Desire is similarly apologetic. He glosses over the darker sides of Blanche’s personality, tactfully considering her to be “one of the dispossessed whose experience has unfitted her for reality.” Both Amanda and Blanche, creations of the male imagination, are given far more credit and understanding than Regina. Granted, these women do not appear to be quite as greedy as Regina; Amanda wants security for herself, through her children, while Blanche wants to return to her glorified past. But it’s worth keeping in mind that Regina wants to make money in order to go to Chicago, where she envisions leading a freer, more cosmopolitan life.

Perhaps a more fitting comparison would be to The Crucible, which features the selfish, destructive Abigail (though even she can be viewed empathetically if one believes that she acted out of desperate love for John Proctor). However, there is barely any mention of the character Abigail—and none at all by name—in the original 1953 New York Times review of The Crucible, written, once again, by Brooks Atkinson. The actress who played her is only briefly referenced, as “the malicious town hussy,” one in a long list of supporting performers. In contrast, Ben Brantley observed how the “frustrated lust in [Abigail’s] condemnation of her fellow townspeople [turned] self-serving duplicity into self-deluding mania,” and devoted multiple paragraphs to that character in his review of the 2002 Broadway revival.

“Malicious” and “hussy” are certainly words that fit right in with the sexist criticism of Regina Giddens, but they are a far cry from the litany of negative barbs ascribed by Brooks Atkinson to Regina. It’s as though it were easier in this case for Atkinson to take the strong, rebellious woman out of the equation, erasing the love triangle at the play’s core. Isn’t that “depriving readers of crucial information,” more so than profanity? Ought we give Atkinson credit for not altogether excluding Regina from his Foxes review, or should we criticize his seemingly limited ability to recognize when unladylike women are central to the plot of a play (and only when the playwright is female too)? Either way, the bar seems pretty low.

It was only when I left off scouring mid-20th century theatrical reviews of plays by men and went further back in time, to Scandinavia in the late 19th Century, that I discovered a true equivalent to the critical response to Regina. The playwright was Henrik Ibsen and the central character in question was Nora Helmer (ironically, there is a new sequel to A Doll’s House on Broadway this season; it was far better received by critics than was the original source material). When A Doll’s House first premiered in Denmark in December of 1879, critics attacked Nora’s moral character. As archived and translated by the National Library of Norway, the Danish newspaper Illustreret Tidende wrote that “her faults were many; she was used to making herself guilty of many small untruths, she taught the children falsehood, she was imprudent and wasteful; her ideal nature she kept hidden, almost willfully.” Such intense scrutiny of a woman’s behavior feels more suited to the muckraking journalists of the early 20th Century, or of 21st century Republican political ads targeting opponents, than theatrical criticism.

In contrast, a century later, A Dolls House had become an established classic and Liv Ullmann was described as giving “a rich, many-layered performance that has about it the quality of a moral force,” in Clive Barnes’ review of the 1975 Broadway production. Critics in 20th century America didn’t judge Nora as harshly as they had when the play originally debuted, and yet they seemed to apply those 19th century standards to Regina Giddens in The Little Foxes. It would seem that the harsh response to Regina’s character was more in line with the critical response to Nora in 1879 than it was to reviews of Nora, or Blanche DuBois, or Amanda Wingfield, or any other strong female character in a mid- to late 20th century production of a play written by a male playwright.

But it is not my intention to throw shade at 19th century Danish critics, nor at The New York Times. They aren’t the only ones fond of derogative words when it comes to Regina. Elizabeth Hardwick of The New York Review of Books called her a “greedy bitch” in reference to the 1967 Foxes revival. While she acknowledged that Regina and her brothers (her fellow co-conspirators in the financial scheme) were “the very spirit of ruthless Capitalism,” Hardwick used the far weaker word “coarse” to describe the brothers, in parallel sentence structure to Regina’s “bitch” adjectives. It is as though she is implying that ruthlessly capitalistic men are coarse while ruthlessly capitalistic women are greedy bitches. It seems Regina’s unladylike behavior has historically perturbed some female theatre critics as well as male. And lest any readers think that the current Foxes revival has escaped the clutches of such language, Deadline’s Jeremy Gerard used the phrase “queen bitch” to describe Regina (while simply referring to her brothers as “greedy”) in his review from April 2017.

To be fair, 21st century critics have spent more time pondering Regina’s psychology and motivations than in the past, when most of the character’s (limited) praise had to do solely with how great actresses played her. In 1939, Atkinson grudgingly admitted Regina “has to be respected for the keenness of her mind and the force of her character,” but attributed all the credit to Tallulah Bankhead’s superior acting skills. In 1981, Rich praised Hellman for “throw[ing] her actors the prime red meat of bristling language,” and appreciated Elizabeth Taylor’s ability to find the humor in Regina. In the 1990s, Ben Brantley proclaimed that despite her horrific behavior, “[f]ew heroines of American theater are half as much fun as Regina Giddens.”

By 2010, critics seemed slightly more aware of the depths yet to be discussed in Regina’s character. Brantley briefly noted “a bottomless hunger that goes beyond her articulated desires,” in Elizabeth Marvel’s 2010 interpretation of Regina, and compared her to a Wall Street executive, though the majority of his review focused on an interpretation that infantilized Marvel’s Regina, depicting her as a “presexual, premoral 2-year-old, a squalling, grabby little girl.” New Yorker critic and 2017 Pulitzer Prize winner Hilton Als wrote an analysis of Regina that had sarcasm practically dripping off the page like wet ink: “Life can be hard on a privileged white woman. Just look at Regina Giddens and all the drama that Lillian Hellman forces her to cope with,” he wrote. Perhaps despite himself, however, Als revealed he occasionally sympathized with Regina, stating that “one feels a pang, every once in a while, for Regina’s dark hopes. How far could she—or any woman—really go in a small Southern town in 1900?” He even suggested that a successful revival, unlike the one he was reviewing, might “marr[y] contemporary feminist politics to Hellman’s insight into the ways in which class and race and need can eat away at an ambitious woman.”

It wasn’t until 2016, when Peter Marks detected “a humanizing rationale” in that “gorgeous enigma,” proclaiming Regina to be “less than a hero but more than a villain,” that the character really found nuanced understanding. For the most part, the reviewers this spring seemed to agree. There were, of course, a fair amount of articles trying to heighten the competition between Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon, who alternate nightly in the lead role of Regina and the supporting role of her sister-in-law Birdie. For reference, I refer you to headlines such as the oddly worded “Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon Are Doing What “Men Do All the Time” in The Little Foxes” or the erroneous “Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon were both up for the lead role Broadway’s ‘The Little Foxes.’ They both got it.” In truth, Linney was offered the role and she suggested that her friend Nixon come on board to share it with her. It would’ve been nice to see more headlines focusing on and commending their friendship, as opposed to the supposed drama, between these two respected actresses.

Regina, at least, seems to be getting her due in this revival, despite Deadline’s “queen bitch” naming calling. Variety’s Marilyn Stasio described Regina as “one of the strongest female characters in all of American drama,” and, “a spirited modern woman cruelly restrained by the social conventions of her time.” Entertainment Weekly’s Isabella Biedenharn praised Laura Linney as Regina for “allow[ing] the audience to feel the pain of knowing what she could have accomplished, the deals she could have closed, if she were born a man.” These depths and dichotomies were explored even further in Alexis Soloski’s insightful New York Times review of the current revival. She wittily opened her piece with the observation that “Regina Giddens is a flower of Southern womanhood. That flower is a Venus flytrap.” Soloski went on to call Regina “one of the stage’s great antiheroines,” noting how her behavior stems from the fact that she is a woman with “greater ambition and less opportunity to satisfy it than any of her kin.” Soloski did not gloss over Regina’s questionable behavior, but she urged readers to “admire her flair and her grit,” even while “loath[ing] her politics and her methods.”

When I saw Foxes back in April, I was struck by an exchange between Regina and her brother Ben, in which Ben tells her she’d “get farther with a smile.” How could that line not stand out, given all of the memes, tweets, late night comedy sketches, and articles all over the world devoted to discussions of Hillary Rodham Clinton’s smile through the 2016 presidential campaign? The New York Times must have been intrigued by this exchange as well. They created a video feature titled “How Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon Smile at Their Enemies.” In the video, Nixon says she considers the ensuing smile that Regina gives her brother Ben to be, ”almost a perversion of a smile. It’s a smile of hate.”

Times critic Soloski called Regina’s smile “weaponized” and considered her ultimately victorious. Unlike similarly formidable theatrical antiheroines Clytemnestra and Lady Macbeth, who were also willing “to sacrifice some essential femininity, rejecting wifely and maternal instincts” in order to pursue their desires, Regina’s “comeuppance never comes.” She actually gets what she wants. As Soloski wryly stated, the play “leaves her finally in command of her body and her fortune and her future. That’ll get her farther than a smile.”

But how far have we come since 1879, 1939, 1967, or 1981, if we are still calling ambitious female characters “bitches”? If our most revered papers still crudely and unnecessarily objectify women’s bodies in theatre reviews and judge respected female directors for being “too serious”? If men are still primarily the ones writing, directing, and reviewing a majority of plays about women that make it to Broadway?

To take things outside the arguably narrow sphere of theatre, how far have we come since Hellman’s HUAC blacklisting America if it is still acceptable for male politicians to interrupt (#manterrupt) one of the few female senators during multiple Senate Intelligence Committee hearings, and to silence their female peers in congress because “she was warned, she was given an explanation, nevertheless she persisted”? How far have we come if we as a society call female presidential candidates “nasty women” who need to smile more and who deserve to be locked up for minor email scandals while we permit men to commit treason many times over while remaining heads of state?

Not very far indeed.