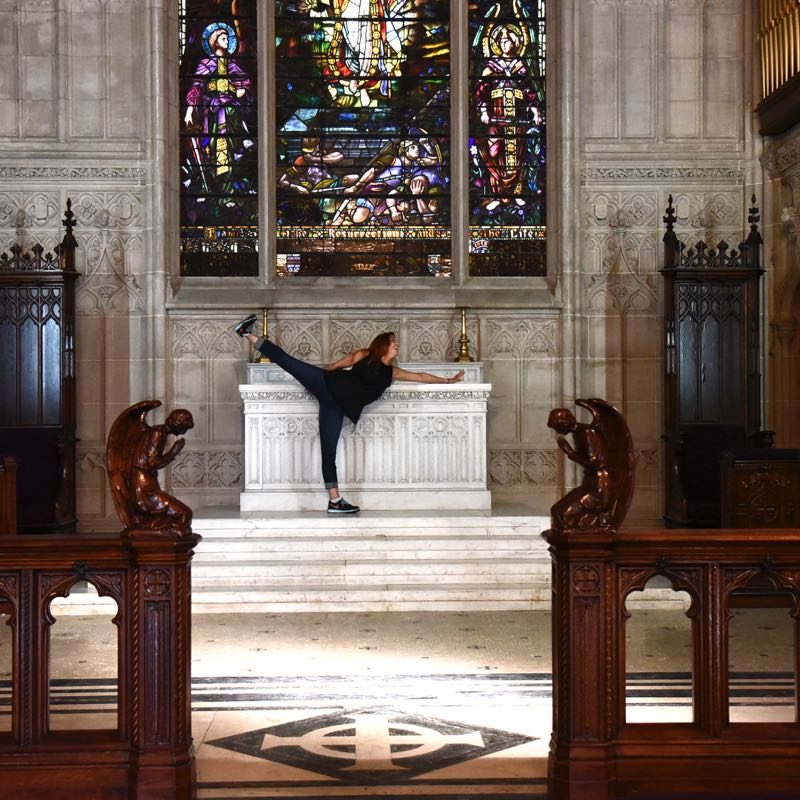

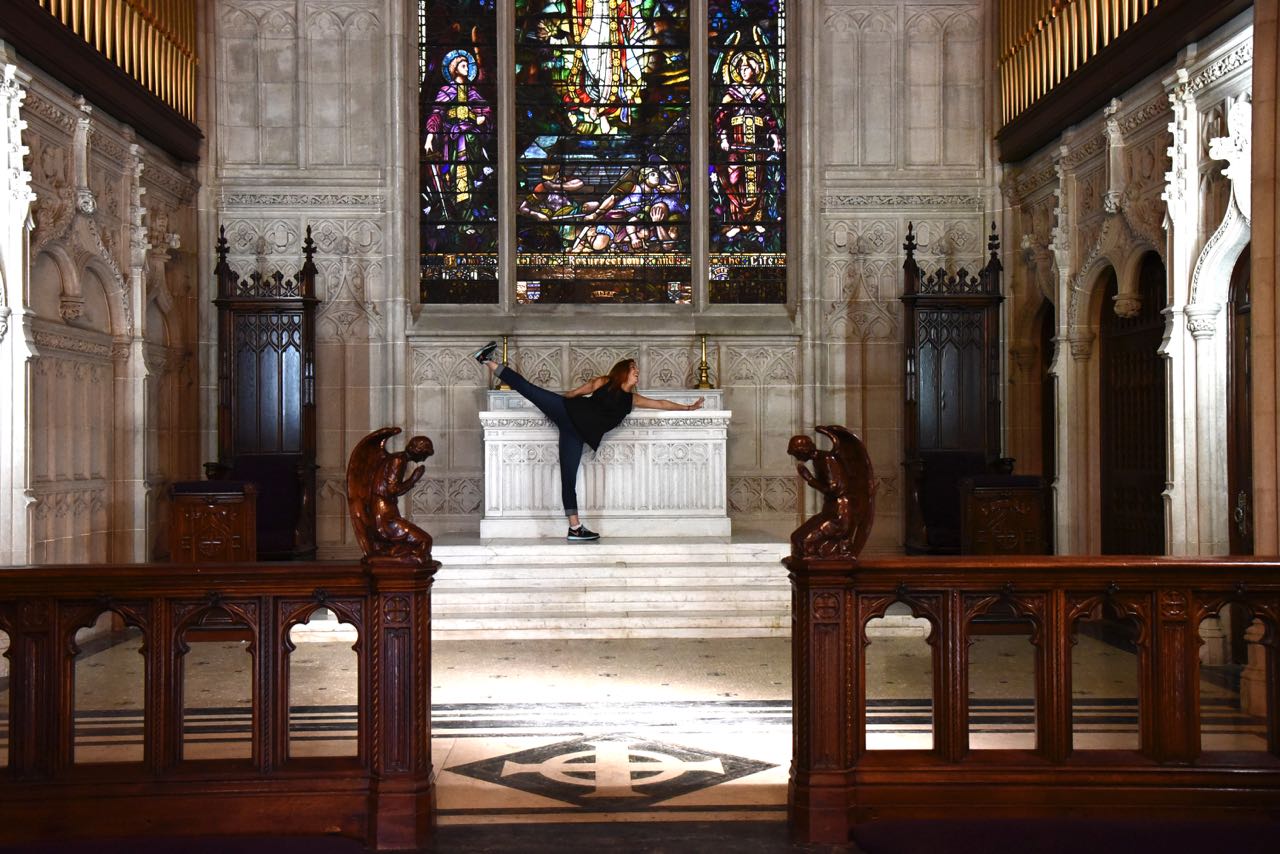

An Interview with Lorin Latarro

Written by Victoria Myers

Photography by Taylor Brandt

July 20th, 2016

Lorin Latarro recently spent a full day inside the Greenwood Cemetery Chapel, which is more time than one might want to spend inside a church in a cemetery (although maybe not… are vampires still popular?), but Lorin Latarro was busy choreographing a video of a pas-de-deux. The pas-de-deux is just one of many projects that Lorin has been busy working on this year (it is the only one that has taken her to a cemetery). Earlier this year, she joined the team of Waitress to choreograph the show for its Broadway bow and making it an all-female creative team. Currently she’s choreographing God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, the final show in the 2016 Encores Off-Center season. After that, she’ll be choreographing Twelfth Night at the Public Theater for PublicWorks and La Traviata at the Metropolitan Opera. After graduating from Juilliard, Lorin danced in the companies of numerous Broadway shows until she switched over to choreography. We talked to her about making the switch to choreography, her process, using art for social change, and more.

Can you tell me a little about the video you just choreographed?

There’s an event called BC Beat and they just pick some choreographers to do a piece of choreography, and I just thought I would do it because I’ve been working with actors at Waitress for a while, so I wanted to work with dancers and just do something more concert-y. And I did this piece. My friend wrote the music, so I had a live cellist and live singers. I wanted to do a male-male duet. When I was at Juilliard, a lot of my friends came out their freshman and sophomore years, and it was very difficult for them. I didn’t go to school that long ago, but I just remember their struggle. And now I teach at Juilliard and the freshmen have been out since they were 9 or 10 or 12. It just struck me for a moment that the world has changed, and I just wanted to create a piece in honor of people who struggled in a way that—certainly here in an urban setting—more people don’t struggle. So that’s what the piece was about. I did the piece, it went very well, and got a nice response. And the guys who wrote it decided they wanted to do a video of it, and that’s what happened. So we tried to sort of up the ante a little bit and put it in a church to give it some symbolism, and the day we filmed it, the Pope came out saying that the Catholic Church owes homosexuals an apology.

Did you find that you had to change some of your process for working in film and not in theatre?

Yes. The process is completely different. You know, theatre is all about prepping and then going. And once you take off it’s like an airplane, and you just sort of have to ramp up for two hours of major physicality as a dancer. In film, you prep, and then you ramp, and then you stop and you relax. And then you ramp, and then you stop. So there are these tiny little bursts of energy versus like, two hours. We filmed all day long, and those guys did that dance 30 times.

Do you find it’s also different in terms of how you’re using space and spatial relationships?

Absolutely. I mean, first of all, depth looks so different on film than it does on stage, so depth is completely used in a different way. And then you just use the architecture of the space, so we changed everything to fit the space. Then we had a drone, so we did some stuff from above.

You mentioned working with actors versus dancers, which in theatre you have been doing quite a bit. How does that change your process in coming up with what they’re going to do, what they’re not going to do, how it tells the story?

Whatever artist is in the room, you use their strengths. And whatever way is the strongest way to tell the story is the way that I like to work. I love working with actors because they do not let you get away with any lies. They want to know the textual information and why you’re choosing to do that at that very moment, and they can also bring several layers of depth emotionally to whatever you’re doing. I also love working with dancers because I love kinetic energy and bouncing around the room. So, I like it both. But for Waitress, we really always came from a place of text and a place of emotion and inner monologue and inner life. And I think for that show it worked very well.

What was your process like for Waitress?

I read the script and then I started listening to the music over and over and over and over again, and I would write down a million ideas. I had this idea of wanting to see her daydreams on stage and that’s how we cracked it. So, as opposed to in the movie where you just go close up on her beautiful little face and she ignores her husband speaking and starts dialoguing and riffing on the new pie she’s going to bake, on stage that’s completely boring. So instead, let her ramble off the ingredients, but while she’s doing that, let us see what she’s really thinking about: escaping him, leaving him, meeting another man, whatever it is.

Are you analytic right away when you’re looking at something?

Yes. Absolutely. I want to tell a story at every given moment, so I use that part of my brain and then I can get creative on top of that. That’s why I like theatre versus concert dance that doesn’t have any meaning. I could listen to a piece of music and start dancing around the room and it could be visually interesting from a kinetic standpoint, but I want to make sure that by the time you are finished watching a dance that you are moved in some way emotionally. And I think the only way to do that is to have some idea of what the dance is about so I can relay that to somebody watching it.

You’re working on God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater for Encores Off-Center right now, which is a super fast process. What was your day like today?

From 10-6 all day today, I sat in a room with two of my associates and we just worked through the whole show. We got halfway through it today, and tomorrow we’ll do the rest of it. We literally just tried to start choreographing it. The three of us were fifteen different people. We’ll do that for the next two days, and then next week for three days I’ll have friends of mine come into the room and I’ll actually try a blueprint of what it looks like on dancers. And then on Friday when rehearsals begin, I will just plow and teach these numbers.

Is it fun to do a show where people don’t have preconceived notions of it or what it should be?

Oh, yeah. I think people are going to be so pleasantly surprised at how beautiful and timely it is. It’s gorgeous. The music’s gorgeous. And I read the Vonnegut book a couple of weeks ago, and it’s beautiful. It’s a beautiful sentiment. And it’s exciting because it was only staged once Off-Broadway and no one remembers it. It’s like, let’s have some fun. I don’t have to contend with like doing “Steam Heat”—how are you going to do that differently and better than Bob Fosse? So, it’s nice to not have to contend with that.

How is that for choreographers when you are doing something that’s a very known quantity and when there’s an existing vocabulary for it?

I think you have two choices. I think one choice is to honor the vocabulary, and maybe either do a version of it that is literally a version of that vocabulary, or take the vocabulary and dial it up and make it feel a little fresh and new. Or two, which I think is the most interesting, take the show, spin it on its head, and come up with a completely different way in and new vocabulary for it. And that would be so exciting. Nobody says that Sweet Charity has to be Bob Fosse, you know?

For you, what is God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater about?

It’s about America right now in 2016. And it is about people who feel disenfranchised. And it’s about Americans who are disenfranchised. And it’s about a man who decides that he’s going to help him for no other reason than it’s the right thing to do. It couldn’t be more appropriate.

What influences do you bring to your work?

I love things with an underbelly. I like things that have a psychology to them because I’m interested in what makes people tick. So I like pulling out on stage what we don’t see on the page. That’s very interesting to me. I like seeing people’s loneliness and isolation; I like seeing people fall in love. I also like ethnicity. I love a vocabulary that stems from Hebrew dance, or Greek dancing, or the Tarantella. I love these sort of old world things that we delve into. Because so much of it is colloquial, and we don’t even realize that it’s coming from something very ancient.

Do you have a dream cultural collaboration?

You know, I have some ideas. I’m a big reader, so a lot of my source material that I have my ideas for come from books. I think books for me are usually my way in.

When you’re reading something do you just think, “Oh! That would be interesting expressed through dance”?

Sure. And what’s great about reading a book versus watching a movie is that you’ve never seen a version of it, and the version in your head. I was the associate choreographer for The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime for Steven Hoggett. I had read the book two years earlier just to read the book, and I was blown away when I started working on the piece because this was not how I saw it at all. And it was just so interesting because what’s beautiful about a book as source material is that everybody can read the same book and see it a different way. So I think what you see on stage can still be so uniquely singular, versus when you see a movie there’s something about that that is a little more visualized in your brain.

You’re very socially conscious.

I do a lot of gun control stuff. And we have a physical approach to that, too, which I did around the country. My sister and I founded Art=Ammo, which is Artists Against Gun Violence, and we created this 200 person sort of flash mob in Times Square. You can see it online at artammo.org. And we did it once in New York, and because it was very visual and very different than talking points and other things that were happening at the time after Newtown, it ended up all over the news—on Rachel Maddow, and on the BBC, and PBS did a special on it, and The New York Times. And then we did ten or twelve more around the country. I’m working on a new project right now—a concert at Radio City on September 25th. Because here we are again. I do feel like as artists it’s really important to be relevant and to have a social commentary on it. It’s one huge way to get past these talking points and people just talking at each other. To cut through all of that and to open it up and see something empathetic on a stage, I think is one of the only ways to shift people’s perspectives.

Is that something you also look for in the shows you work on?

Absolutely. And I hope that I’ll get more and more opportunities as people start to trust me with material more. I feel like I’m just starting my career.

Is there a particular way you like to work with a director?

The director is King and Queen, and I am very happy to work whatever way they need me to work with them. I like collaborating, so it’s not hard for me. I like really prepping, because I feel like if you prep, you can always change things. I’m never married to anything, but I like being uber prepared so you can get to the fifth or sixth or seventh layer of something as opposed to just the first layer of something. And I like talking and using pictures, and just talking through things together and making sure that I’m inside his or her brain to make sure that the kind of things she sees as a whole, I’m fitting under that umbrella in the physical matter.

You went to Juilliard. Something that comes up a lot in interviews is developing as a person while also developing as an artist. In a conservatory setting, what was that process like for you?

Whatever it says about me, good or bad, I loved every second of Juilliard. And found it a warm, fuzzy environment. Now, you can take that to Freud and decide what that means. But I came from a family of doctors—my brothers are both surgeons, my dad was a dentist, my mom was a very smart woman, my sister went to Harvard—so I had to differentiate myself through dance. When I got to Juilliard, it just opened up a whole world for me. It was like unzipping a seal skin and kind of being in my own body for the first time in my life. So I very much loved it. Growing up in New Jersey was hard for me because it is a very specific political environment that I didn’t agree with, but I didn’t know how to articulate that as a young girl. Getting to Juilliard and being around people who were like me was mind-blowing. And it was international, so my sophomore year I went to Europe for the first time and traveled around. It was just four years of constant learning. I mean, class to city—the neurogenesis going on in my brain was constant. I was a good dancer but not a great dancer, so I also was learning so much as far as dance goes, and seeing everything. I mean, it was before the internet was gigantic, so I got to see Jiri Kylian for the first time working with him. And Pina Bausch, and Nikolais/Louis and all these things that were like, mind-blowing. I mean absolutely mind-blowing. So for me, it was four years of absolute growth. And socially, from an activist standpoint, I certainly learned a ton and got to meet people who were not like me. And I would say that as far as relationships go and that kind of growing up as a person, that might have been a little delayed. Ironically, my husband is a doctor also.

When you’re young and studying a profession where there’s a lot of pressure on your physical appearance and people telling you all sorts of things about yourself all the time, what’s that like? That doesn’t happen so much if you’re studying medicine or law.

Look, as a dancer, you don’t see yourself as an objectified object. And I will hope that more people than not think that also, because you’re an athlete and you’re an artist and are working your body, and you shapeshift to become whatever the choreographer’s asking you to be. With that in mind, you’re constantly looking at a mirror. I mean, the feminist in me is going, you’re constantly looking at a mirror and you’re constantly in these tiny little outfits. You’re constantly being called a girl—you’re subordinate in the very definition of some level of what you do for a living. So, it worked for me a very long time. And when it stopped working for me is when I rolled into becoming a choreographer and it’s been really freeing. I don’t have to look into the mirror anymore; I look out into the universe and the world instead. So, I guess I was lucky enough to unconsciously become conscious at the right time in my life before anything poisonous happened, but I do think it’s something to be highly aware of.

I’m assuming that’s something that you think about now when you’re working with dancers?

Absolutely. And I hate to see body shaming and I hate to see girls that are too thin or won’t eat lunch.

Is that dichotomy of dance being super athletic and also, especially in some Broadway shows, wearing very little, weird?

Sure. I was in Spamalot. But you’re also an actress and there’s also comedy to that. But, yeah, there’s an element of that for sure. While I was in it, I just never felt that way. It’s something to think about some more actually, I think. It’s something that can be dialogued more. But, you know, I said very proudly that there are no bevels in Waitress. And I meant it. It’s about real women and how real women behave on stage.

When you actually moved into musical theatre from Juilliard, how was that for you?

I danced for Martha Graham and for MOMIX right out of Juilliard, and then I auditioned for Swing and I got into it. And that was the hardest show to date that I’ve ever done. It was very difficult, but I had a blast. And I just loved it because I love singing and I love acting, so I got to do all these things and stay in New York and not be living out of a suitcase. And when I got bored, I auditioned for another Broadway show, and luckily, gratefully, I got to do many things.

How was that transition from dancer to choreographer? Did you find people were like, “That’s great! You should definitely do that!”? Or did you find there was some resistance? A little bit of both?

I found a little bit of both. One thing I experienced was that people saw me in a certain way and everybody knew me already. I’d worked with so many directors and producers as a dancer, as an understudy for one of the lead roles. So to shift their perception of me took some real… I had to prove it. And in a way, I think it might be harder to have to shift perspective on somebody versus coming in fresh. If I had just come from California and told people I was this fantastically intelligent choreographer who knew lots of different kinds of dance, I might have had quicker success. It was almost like, “Oh, Lorin? Oh my god, I love her! She’ll do anything!”

Do you think it’s harder as a woman to change people’s perceptions?

I wonder. I wonder. Dot dot dot…

Did you find that maybe part of that had to do with being in one position where it’s a lot of “Yes, I’ll try that! Yes, I’ll do that!” to all of the sudden being the one in charge and telling people what to do?

Sure, but you know what I’ve learned? That it’s actually a really useful skill to be in the room with a director, and he has an idea or she has an idea, and instead of me being like, “No!” I go, “Let’s try it! Sure!” Because that is my personality. What I learned with Diane [Paulus] was that she will do that. And the first day she did it, it caused a lot of anxiety for me. Because I did a number and I showed it to her and she pulled it apart, and I completely panicked. Then she went, “Nope. Your way was better. Let’s put it back.” And once she did that, I was like, I get it. She’s smart enough to know that she can try something and smart enough to know what’s better. So then the next day we tried something, she pulled it apart, and her idea was better. But after I figured that out, my anxiety level went way down because it was like, “Oh. There are other ways.”

Something that comes up lot a lot with directors is how they learned to be the authoritative voice in the room and the different ways of doing that. Was that also something that you had to go through when transitioning?

Yes. I like being a leader. And I like being a benevolent leader. And I do believe that you get more out of people when you trust them and you ask what they think and you ask them to bring their best selves into the room. So it’s easy for me in that sense. I treat people the way I wanted to be treated as a dancer or as an actress. So it’s been really satisfying. Because I’ve been in rooms where you’re getting yelled at, and that stuff stays inside the piece—it gets injected inside the piece, and then all of the sudden you’re doing the show eight times a week and you’re feeling crummy. And you’re like, “Why am I feeling crummy?” Because our brains absorb those things.

Do you find that it’s harder to get people to see you doing different types, different styles of work than perhaps if you were a man coming in?

Well, let’s look at my resume. Let’s see: Fanny, Waitress, Beaches, Saving Amy. It’s sort of like, “Oh, it’s a show about a girl that’s got a girl choreographer.” Which, thank goodness in that case, but I want to do a show about men going off to war. That’s why I wanted to do the gay men’s duet. I want to be able to be at the table for all these things. And I also want to make sure that women’s stories are told. And if there are more female writers and females at the table, that table might come through in a way that might be a unique perspective. Jessie Nelson—the writer of Waitress and a very smart woman— and I were asked if being a woman, we have a better point of view about a woman’s story. And I said, “Well you might. There might be something that you understand inherently that you’ve never said out loud that you’ve never been able to put in there in spite of it.” And Jessie Nelson said, I thought very intelligently, “As artists, our job is to be as empathetic as possible and to tell stories, so I would hope to think that a man could tell this story as well as a woman, and a woman can tell a man’s story as well as a man.” Which I thought was a very inclusive sentence. And wouldn’t it be nice if we could get there one day.

How can the theatre community improve the way it develops new work?

I’m involved in SDC, our union, and I say this all the time: the choreography has to be involved in the development of the project, otherwise you will never get deep choreography. If you develop a show and you just look at the book and you just look at the songs, and then four weeks before it opens on Broadway you pull a choreographer in to put the dance steps on top of it, you won’t get Curious Incident. The way the National Theatre works in London, or dance companies who do theatre movement, is they work from the very beginning. I feel like our unions have a very hard time figuring out how to get dance involved very early because it’s so expensive. So it’s something that I think needs to be really talked about. Usually you do readings first and then, if you have money, you do a workshop and a lab. Sometimes you don’t even get that. But I feel like the only way to really sit down and look at a book and say, “Okay, you can take this whole scene and get rid of all this dialogue and I can choreograph this.” Or, “Let’s find the movement style that works the entire piece.” It takes a long time to develop that. I think we need to put dance early in the process, not late in the process. And the problem with it from a business standpoint is that it’s expensive. So, I think it’s something to continue to dialogue about in our industry. How do you push the envelope in a musical theatre sense without having the physical part of theatre?

What’s something you think the theatre community can do to improve gender equality in theatre?

Give us a chance. You know, just keep giving us a chance. The only way to get better is to continue to work. And every experience I’ve had, I have learned something from, and my toolbelt is very full. Just keep us at the table. We have a point of view, period. And I think it’s a useful one. I think to get to the next story about women, we have to get through this story first and start to see on stage what we’d like to see in real life.